Abstract

This brief study looks empirically at the relationship between federalism, decentralization, and statehood. This relationship is often studied by case studies, rather than looking at the subject from a broader empirical perspective. The analysis is based on a sample of 49 countries from different world regions, using data from the Fragile States Index (FSI) and the Regional Authority Index (RAI). The findings show that the degree of statehood is not related to a federal structure of a state, but related to the degree of decentralization.

Introduction

This short contribution looks empirically at the relationship between federalism, decentralization, and statehood. It argues that the degree of statehood is not related to a federal structure of a state, but related to the degree of decentralization. The analysis is based on a sample of 49 countries from different world regions, using data from the Fragile States Index (FSI) and the Regional Authority Index (RAI).

In this analysis I especially focus on the relationship between statehood and decentralization. Therefore, I use as a guiding hypothesis an assumption made by Fukuyama (2005: 91ff). In his study on state-building he argues that decentralization might lead to a higher degree of corruption and clientelism, arguing that “the delegation of authority to state and local government in developing countries often means the empowerment of local elites or patronage networks that allows them to keep control over their own affairs, safe from external scrutiny” (Ibid.: 97). He thereby refers to the case of Indonesia after the Suhartu regime. Due to the constitutional changes fostering a higher autonomy on the provincial and local level, a higher degree of corruption could be found (Ibid.: 97f.).

On the other hand Fukuyama (2005) argues that in developed countries decentralisation actually improves statehood and enables the state to be better organised, more efficient and more open to societal, economic and administrative experimentation. Therefore we can assume that the relationship could be both positive and negative, depending on the degree of development of the countries.

Measuring statehood, federalism and decentralization

Measuring statehood

For the measurement of statehood I use data from the Fragile States Index (FSI), created by the Fund for Peace (2020a, 2020b, 2020c). The FSI uses a broad definition of measuring statehood, which includes economic, political, social and security aspects. I refer to the idea of a thin concept of statehood exemplified elsewhere (Schlenkrich et al. 2016: 243ff)[1] which argues that statehood consists in a minimal sense of the functioning of two dimensions: the monopoly on the use of physical force, i.e. the states capability to overcome competitors (e.g. rebel groups or organized crime) that threaten its monopoly on the use of physical force; therefore this security function can be understood as the “state’s prime function” (Rotberg 2004: 3). Second, the state needs an administration which is able to deliver basic goods to the citizens and has the capacity to execute the laws and policies of the government. Additionally, the monopoly on the use of physical force is a necessary condition of a functioning state, i.e. without it the administrative branch would not be able to work.

Based on this thin concept of statehood I only use two variables of the FSI. To measure the monopoly on the use of physical force I use the indicator Security Apparatus, which “considers the security threats to a state, such as bombings, attacks and battle-related deaths, rebel movements, mutinies, coups, or terrorism” and “takes into account serious criminal factors, such as organized crime and homicides, and perceived trust of citizens in domestic security” (Fund for Peace 2020d). To measure administration I use the indicator Public Services, which “refers to the presence of basic state functions that serve the people” (Fund for Peace 2020e), e.g. health, education, sanitation, and electricity and power.

Since the logic of the FSI scores is “the lower the score, the better” (Fund for Peace 2020a: 3), I reverse the polarization so that the higher the score (maximum = 10) the higher the degree of statehood in both dimensions. The total score of statehood is the result of a multiplication of both dimensions – due to the idea that security is a necessary condition for statehood – and the square root is taken so that we receive a scale that ranges between 0 (no statehood) and 10 (high degree of statehood).

Measuring federalism and decentralization

For the measurement of federalism I refer to the classification of countries made by Schakel (2019) and distinguish federal countries from non-federal countries. Thereby I use the concept of federalism as suggested by Hooghe et al. (2020). They write that in a federal system “the centre cannot change the [territorial] structure of authority unilaterally” (2020: 198), it “is portioned in regional units” (Ibid: 198) and that “government functions are divided and sometimes shared between the central government and regional governments, and this dual sovereignty is constitutionally protected against change by either the centre or the regions acting alone” (Ibid: 198).

Decentralization, on the other hand, “refers to the shift of authority towards regional or local government and away from central government” (Hooghe et al. 2020: 197). These shifts can be political, fiscal or administrative (Ibid: 197). For measuring decentralization I use country data from the Regional Authority Index (RAI) (Hooghe et al. 2016; for data download see http://garymarks.web.unc.edu/data/regional-authority/). The RAI consists of two dimensions: the degree of self-rule, i.e. “the authority exercised by a regional government over those living in its territory” (Schakel 2019) and the degree of shared rule, i.e. “the authority exercised by a regional government or its representatives in the country as a whole” (Schakel 2019). The total RAI is the sum of both dimensions (self-rule & shared-rule) and “scores may vary in between zero (no regional government) to a maximum of 30” (Schakel 2019). For my purpose the RAI indicator is transformed into a scale that ranges between 0 (no regional government) and 10 (high degree of regional authority).

Due to the combination of both data resources and the categorization of federal states by Schakel (2019) 49 countries of different world regions (e.g. Europe, Northern America, Oceania, Asia, Latin America) in the year 2010 (last data point of the RAI dataset) are compared. This means that this study is not representative but gives a first explorative insight into the relationships of statehood, federalism, and decentralization.

The following federal and non-federal countries are included (see Schakel 2019; Israel has been excluded due to non-comparable FSI data):

Federal countries: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Malaysia, Mexico, Switzerland, United States, and Venezuela.

Non-federal countries: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Finland, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Iceland, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, and Uruguay.

Is there a difference in the degree of statehood between federal and non-federal countries?

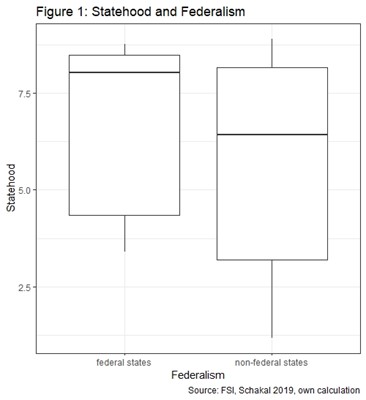

The boxplot in figure 1 shows the degree of statehood in both federal and non-federal states in the sample. First, the median value of the degree of statehood is higher in federal states than in non-federal states. Second, there is much variation of cases in each group. Therefore, the F test is used to compare the two groups. The results show (F = 0.82703, p = 0.77) that the two groups do not statistically differ concerning their variation on the degree of statehood. This means in the sample the degree of statehood does not depend on whether a state has a federal structure or not.

Is there a relationship between statehood and decentralization?

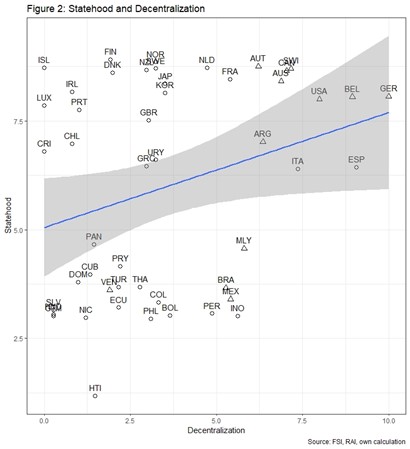

As a next step I take a look at the relationship of decentralization and statehood and therefore picking up the hypotheses by Fukuyama. The correlation of statehood and decentralization is significant, positive, but also weak (Pearson’s r = 0.29, p = 0.04). Figure 2 gives some further insights. First, the majority of cases in the sample (n=34) shows a degree of decentralization less than 5.0, whereas concerning the degree of statehood the majority of cases (n=28) is above 5.0. Second, only a few cases (n=9; Panama, Greece, Uruguay, Argentina, Italy, United States, Belgium, Spain and Germany) are almost close to the regression line, whereas most of the cases are deviant cases. Third, of the twelve federal states in the sample (pyramid shape) the majority of cases (n=8) shows a high degree of statehood (> 5.0), whereas only four cases (Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico and Malaysia) show a lower degree of statehood.

This finding shows that Fukuyama’s argument could not be clearly confirmed. In fact, not only is the overall correlation positive, but also the case of Indonesia which he uses for his argumentation is an outlier concerning the relationship of decentralization and statehood. The degree of corruption might explain the Indonesian case and could serve as a possible intervening (maybe mediating or moderating) variable in future analysis. But also the degree of development must be tested because the cases in the sample show that countries with a higher level of development and a higher degree of statehood can be found with lower (e.g. Finland, Luxembourg) or higher degrees of decentralization (e.g. Germany, United States).

In a next step, the 49 cases are classified concerning their degrees of statehood and decentralization (see Table 1). Systemizing the cases that way helps to identify some patterns. The majority of states with a high degree of statehood are non-federal states. With the exception of Venezuela all other federal countries show a high degree of decentralization in 2010. Additionally, most of the federal cases having a high degree of decentralization show also a high degree of statehood.

| Table 1: Classification of countries based on degrees of statehood and decentralization | |||

| Degree of Statehood | |||

| low (< 5.0) | high (> 5.0) | ||

| Degree of Decentralization | low (< 5.0) | Dominican Republic, Cuba, Panamá, Peru, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Turkey, Thailand, Colombia, Bolivia, Philippines, Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti, Paraguay, Honduras, Guatemala (n=1/17) | Iceland, Luxembourg, Ireland, Finland, Denmark, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Japan, South Korea, Uruguay, Greece, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Portugal, Chile, Costa Rica (n=0/17) |

| high (> 5.0) | Brazil, Mexico, Malaysia, Indonesia (n=3/4) | France, Australia, Austria, Argentina, Italy, Canada Switzerland, United States, Belgium, Spain, Germany (n=8/11) | |

| Source: own classification based on the results of figure 2; countries in italics are federal countries, n=49; numbers in brackets (no. of federal states in the category/total no of states in the category). | |||

Based on the suggested classification the cases can be grouped by the degree of statehood into low and high statehood. The boxplot in figure 3 supports our suggestions. The median values of the degree of decentralization vary between these two groups, showing that the median is lower in cases with low statehood than in cases with high statehood. This time, the F test shows that the two groups differ significantly from each other (F = 2.6651, p = 0.03).

Conclusions

This brief empirical analysis gives us a first insight into the relationship between federalism, decentralization, and statehood. First, there is no clear relationship between federalism and the degree of statehood. Only a minority of the cases in the sample with a high degree of statehood are federal states. On the other hand, the majority of the federal countries in the sample show a high degree of statehood. Second, there is a positive relationship between decentralization and statehood. But, since most of the cases have a low degree of decentralization, it is not possible to argue that decentralization is a necessary condition for improving statehood. Nonetheless, the analyses shows that in some cases not only federalism, but instead decentralization might relate positively to the degree of statehood.

Furthermore, these findings lead to two interpretations in the case of possible causal relationships: First, one could argue that a higher degree of decentralization might lead to a higher degree of statehood. This might be because the different self-governed territories might try to compete in serving their own citizens through improving their state capacities and thereby strengthening the state as a whole. Second, a higher degree of statehood might be a necessary condition for a higher degree of decentralization. This means that if the state in general has not enough capacity by itself – and therefore no functioning state bureaucracy for example – the decentralization might widen the state weakness. Gerring et al. (2011) discuss the relationship of historical statehood and several measures of political (de)centralization (federalism, autonomous regions, and decentralized revenue) based on data for 89 countries. Their results show that statehood and decentralization are positively correlated and would therefore strengthen this hypothesis.

State-building in post-conflict societies

Federalism and decentralization are key concepts in the study of post-conflict societies, especially concerning cases of ethnic conflict (e.g. Anderson 2013, 2016; Brancati 2006, 2009; Keil 2016; Wolff 2010, 2011). Additionally, other studies analyze the relationship of state failure and ethnic conflict (e.g. Bates 2008). Concerning the issue of state-building in post-conflict societies, there might be two pathways to suggest. The first could be described as state-building before federalism/decentralization. This stepwise-approach suggests that without a certain degree of statehood, i.e. a high degree of security and administrative capacity on the national level, it will not be possible to build a federal system that might work in the long run for the whole country. In this case, a high degree of statehood is a necessary condition for establishing a federal system.

The second path could be described as state-building through federalism/decentralization. This parallel-approach suggests that both statehood and federalism are intertwined and should be constructed at the same time. Thereby the state capacity of the whole country rises by building a federal system. In this case, a high degree of statehood might be a helpful precondition, but it is not a necessary condition. Both pathways might lead to different outcomes concerning the rebuilding of post-conflict societies and should therefore be studied in more depth.

Additionally, we should consider the capacity of local self-governance as a third option. As Pfeilschifter et al. (2020: 15-16) argue, there are four different relationships between the state and local self-governance: they can be substitutive, subsidiary, complementary, or contrary. A further investigation of these relationships in combination with the concepts of federalism and decentralization might be very fruitful. Mohamad-Klotzbach (2020: 11) suggests, that local self-governance might work as a more complementary, subsidiary or even contrary mechanism in federal or decentralized states. It can be either a resource or a danger for the state.

Next steps

This brief study might be used as a starting point for a deeper understanding of the relationship between these three concepts. For further analysis, a larger sample should be used including also countries from the MENA region or Sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, the relationships between the subdimensions of decentralization (self rule & shared rule) and statehood (security & administration) could be addressed. Third, the degree of societal development and the degree of corruption should be taken into account, serving as moderating or mediating variables. Fourth, studying the relationships between statehood, federalism, decentralization and local self-governance might bring new insights on the societal capacities to solve problems. Finally, comparative analysis as either intra-regional or cross-regional comparison (see Basedau/Köllner 2007: 110) could be useful to gain more insights into the interdependence of federalism, decentralization, and statehood.

[1] In this study I use a simplified version of the Contextualized Index of Statehood (CIS) by just looking at the physical and administrative capacities and not taking into account the physical and administrative challenges (see Schlenkrich et al. 2016: 248ff.).

Literature

Anderson, Liam D. (2013) Federal Solutions to Ethnic Problems. Accomodating Diversity. London and New York: Routledge.

Anderson, Liam (2016) Ethnofederalism and the Management of Ethnic Conflict: Assessing the Alternatives. Publius: The Journal of Federalism 46: 1–24.

Basedau, Matthias, und Patrick Köllner (2007) Area Studies, Comparative Area Studies, and the Study of Politics: Context, Substance, and Methodological Challenges. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 1: 105–124.

Bates, Robert H. (2008) State Failure. Annual Review of Political Science 11: 1–12.

Brancati, Dawn (2006) Decentralization: Fueling the Fire or Dampening the Flames of Ethnic Conflict and Secessionism? International Organization 60: 651–685.

Brancati, Dawn (2009) Peace by Design. Managing Intrastate Conflict through Decentralization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fukuyama, Francis (2005) State Building. Governance and World Order in the Twenty-First Century. London: Profile Books.

Fund for Peace (2020a) Fragile States Index – Methodology. Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/methodology/ (Accessed: 24.3.2020)

Fund for Peace (2020b) Fragile States Index – Indicators. Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/indicators/ (Accessed: 24.3.2020).

Fund for Peace (2020c) Fragile States Index – Data Download. Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/excel/ (Accessed: 24.3.2020)

Fund for Peace (2020d) Fragile States Index – Security Apparatus. Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/indicators/c1/ (Accessed: 24.3.2020)

Fund for Peace (2020e) Fragile States Index – Public Services. Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/indicators/p2/ (Accessed: 24.3.2020)

Gerring, John, Daniel Ziblatt, Johan Van Gorp, und Julián Arévalo (2011) An Institutional Theory of Direct and Indirect Rule. World Politics 63: 377–433.

Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, Arjan H. Schakel, Sandi Chapman Osterkatz, Sara Niedzwiecki, Sarah Shair-Rosenfield (2016) Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, Arjan H. Schakel (2020) Multilevel governance, in: Caramani, Daniele (ed.) Comparative Politics. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 193-210.

Keil, Soeren (2016) Multinational Federalism in Bosnia and Herzegowina. London and New York: Routledge.

Mohamad-Klotzbach, Christoph (2020) Zum Zusammenhang von Staatlichkeit und lokalen Selbstregelungen: Einige theoretische Überlegungen. LoSAM Working Papers 3. https://doi.org/10.25972/OPUS-21951

Pfeilschifter, Rene, Hans-Joachim Lauth, Doris Fischer, Eberhard Rothfuß, Andreas Schachner, Barbara Schmitz, Katja Werthmann (2020) Local Self-Governance in the Context of Weak Statehood in Antiquity and the Modern Era. A Program for a Fresh Perspective, English edition. LoSAM Working Papers 1. https://doi.org/10.25972/OPUS-20737

Rotberg, Robert I. (2004) The Failure and Collapse of Nation States. Breakdown, Prevention, and Repair, in: Robert I. Rotberg (ed): When States Fail. Causes and Consequences. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 1-49.

Schakel, Arjan H. (2019) Measuring Federalism and Decentralisation, in: 50 Shades of Federalism. Available at: http://50shadesoffederalism.com/theory/measuring-federalism-and-decentralisation/

Schlenkrich, Oliver, Lukas Lemm, and Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach (2016) The contextualized index of statehood (CIS): assessing the interaction between contextual challenges and the organizational capacities of states. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 10: 241–272.

UNDP. 2010. Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations – Pathways to Human Development. New York. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2010

Wolff, Stefan (2010) Approaches to Conflict Resolution in Divided Societies. The Many Uses of Territorial Self-Governance. Ethnopolitics Papers No. 5. Available at: https://www.psa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/page-files/EPP005_0.pdf

Wolff, Stefan (2011) Post-Conflict State Building: the debate on institutional choice. Third World Quarterly 32: 1777–1802.

Further Readings

Bates, Robert H. (2008) State Failure. Annual Review of Political Science 11: 1–12.

Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, Arjan H. Schakel, Sandi Chapman Osterkatz, Sara Niedzwiecki, Sarah Shair-Rosenfield (2016) Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lambach, Daniel, Eva Johais, Markus Bayer (2015) Conceptualising state collapse: an institutionalist approach. Third World Quarterly 36: 1299–1315.

Rotberg, Robert I. (ed.) (2004): When States Fail. Causes and Consequences. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Schlenkrich, Oliver, Lukas Lemm, and Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach (2016) The contextualized index of statehood (CIS): assessing the interaction between contextual challenges and the organizational capacities of states. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 10: 241–272.

Dr. Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach is a Political Scientist at the University of Würzburg, specialized in the field of Comparative Politics. He is working on statehood and state failure, democratization, political culture, political parties and voting behavior. Currently he is the general coordinator of the interdisciplinary DFG Research Unit 2757 “Local Self-Governance in the context of Weak Statehood in Antiquity and the Modern Era” (LoSAM) at the University of Würzburg, see: https://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/en/for2757/losam/ .

Dr. Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach is a Political Scientist at the University of Würzburg, specialized in the field of Comparative Politics. He is working on statehood and state failure, democratization, political culture, political parties and voting behavior. Currently he is the general coordinator of the interdisciplinary DFG Research Unit 2757 “Local Self-Governance in the context of Weak Statehood in Antiquity and the Modern Era” (LoSAM) at the University of Würzburg, see: https://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/en/for2757/losam/ .