Abstract

Nepal and Myanmar both committed to establishing federalism in response to ethnic conflict and a secession risk. However, while Nepal has successfully enacted a federal constitution following a participatory process, Myanmar’s elite-based negotiations have slowed considerably. The management of the secession risk is the key issue pervading the federalism debates in these countries. This is especially manifest in decisions about how and where to draw provincial boundaries (ethnic versus territorial federalism) and the division of powers. Such design features can help overcome the perception within Myanmar’s military that federalism will lead to secession, which remains a significant hurdle.

Introduction

Ten years ago, two countries in Asia took significant steps on their journeys towards federalism. In Nepal, a newly elected constituent assembly declared, as its first act, the country to be a democratic, secular and federal republic. In Myanmar, a new ‘quasi-federal’ constitution was approved in a (dubious) referendum, as one step in a ‘managed transition to democracy’.

There are other similarities between Nepal and Myanmar. Both are developing countries, home to more than 100 different ethnic groups and with a history of centralised authoritarian rule interspersed with short-lived democratic periods. Significantly, their steps towards federalism have been taken in response to ethnic conflict.[1] Yet, they have not walked in unison.

Since 2008, Nepal has completed a new three-tiered federal constitution, held elections for each tier and established its local and provincial structures. Conversely, despite a much-heralded democratic change of government in 2015/16, Myanmar’s federalism debate remains mired in the legacy of its independence process and the ensuing – and ongoing – internal conflicts.

Secession Risk and Holding-together Federalism

The paradox of federalism[2] (Erk & Anderson, 2009) will be familiar to many readers. It is especially relevant to ‘holding-together’ federal systems like Myanmar and Nepal, where it often manifests as a question about secession. In such holding-together contexts, the secession risk is both the key reason for and against federalisation (Breen, 2018b). It is less obvious in the Nepal case, but no less pertinent. The secession risk pervades both the question of whether or not to establish federalism, as well as how it should be designed.

A secession risk can be managed by institutional design. For example, whether provinces[3] are more or less ethnically homogenous, the revenue and power-base of the provinces, and the emergency intervention powers of the central government. Therefore, once federalism is agreed, debates focus on how and where to draw the boundaries of provinces, in particular whether they should be ethnically- or territorially-based, and what powers provinces should have – in particular, law and order and revenue.

Agreements for Federalism

Myanmar

In Myanmar, federalism debates have been longstanding, yet suppressed. In 1947, the Panglong Agreement was reached between representatives of the Bamar ethnic group and three other large ethnic groups. It promised full autonomy in internal affairs, which was taken to mean federalism, and there was an apparent side-agreement on a secession right (Williams, 2017). However, the agreement was never properly implemented, and the semblance of autonomy in the subsequent constitution was revoked by the military in 1962 following a threat by one of the ethnic groups to exercise its secession right. Since then, the promises of Panglong, and its sometimes-contradictory prescriptions, have hung over the heads of state-builders, ethnic political actors and the military (Walton, 2008).

Federalism is now a commitment of all key actors in Myanmar. In the lead up to the 2015 election, several ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) and the government signed a national ceasefire agreement, which recorded a commitment to ‘Establish a union based on the principles of democracy and federalism’ (Item 1.a., Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the Ethnic Armed Organizations). But there was little in the way of detail and the agreement was ‘a first step’ only (Item 1.b.).

The 2015 election was a pivotal moment in Myanmar’s transition. The National League for Democracy, headed by Aung San Suu Kyi promised ‘genuine federalism’ and won in a landslide. However, the military retained 25% of the seats in parliament, and thereby a veto right on constitutional change.[4] Many EAOs maintained their arms and continue to agitate, politically and militarily, for federal constitutional change. Moreover, discussion of federalism was effectively banned until recently, and so there is a knowledge gap and very little public participation – especially when compared with Nepal (see Breen, 2018c, pp. 127-134). Instead, the 2008 constitution (drafted by a constitutional convention working within tight parameters established by the military) now forms a clear basis for further federalisation.

Nepal

In Nepal, the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Agreement and 2007 Interim Constitution provided the roadmap for federalisation. They included commitments to state restructuring and political inclusion, but little detail or direction on the nature of a future federal system (Item 3.5, Government of Nepal & Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), 2006). This task was left to a constituent assembly elected in 2008 (and again in 2013).

The constituent assembly committed formally to federalism in 2008, in response to uprisings in the Terai (the southern plains adjoining India) and associated secession threats. It instigated a participatory constitution-making process, punctuated by thousands of public meetings, democratic dialogues and education programmes, which together had an important influence on the final outcome (Breen, 2018a). The vestiges of Nepal’s authoritarian past were well and truly side-lined by this point and had no role in the federalisation process.

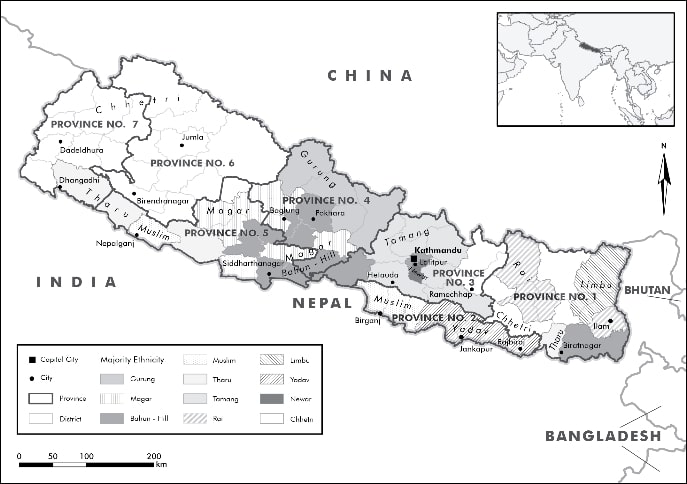

Ethnic Federalism and the Division of Powers

Nepal’s constituent assembly was able to agree most issues within a two-year period. However, it was a further five years before the new numbers and boundaries of the provinces were agreed. The political parties bickered about whether there should be ethnic federalism or territorial federalism – or in their words, whether states should be based on identity or viability (Breen, 2018a). Some (e.g. Lawoti, 2014) would argue that this can be reduced to an argument about maintaining the hegemony of the dominant group, or not. However, at its most fundamental, it is a question of secession risk.

A large proportion of the country was unsatisfied with the final outcome, because it did not include a Madhesi province in the west, or one single Madhesi province running across the Terai (International Crisis Group, 2016). But creating such a state would create an unacceptably high secession risk,[5] reigniting persisting fear since a supposed Indian annexation plan in the 1970s.

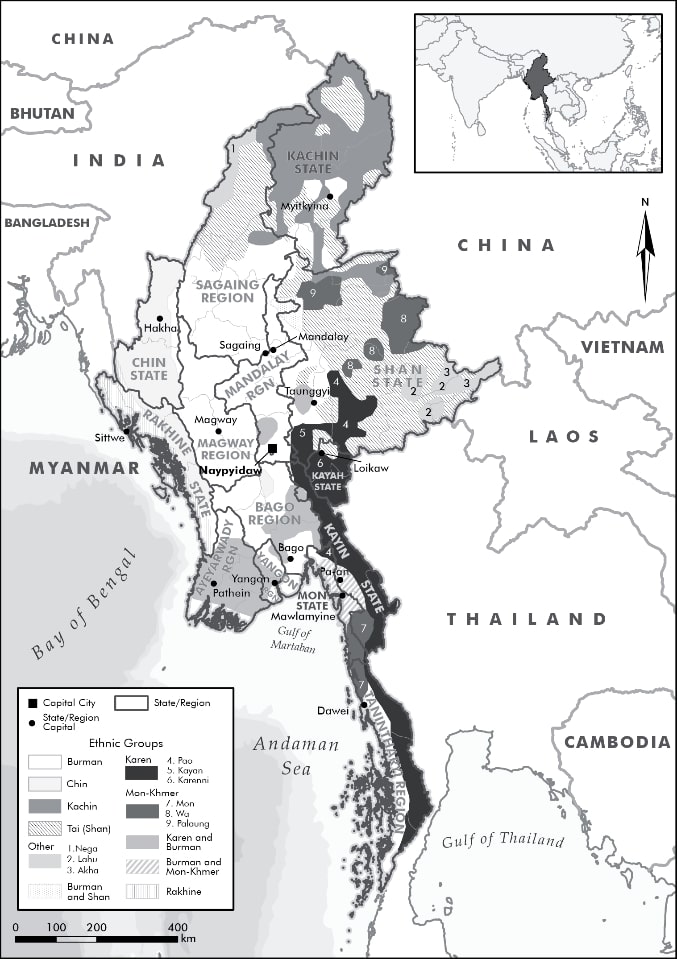

In Myanmar, there are longstanding provinces (states and regions) and there is much resistance to change. However, debates are no less vehement. One issue that causes much consternation is a proposal to merge existing regions (that are mixed or have a Bamar majority) into a single Bamar state. This would meet the rhetoric of the founding father of modern Burma, Aung San, that ‘if the Bamar get one Kyat [unit of currency], then you will get one Kyat’ (cited in Walton, 2008, p. 897). In other words, one ethnic state for each (major) ethnic group. But the Bamar comprise around two thirds of the population, and the creation of a single Bamar province would violate Hale’s (2004) contention that ethno-federations with a ‘core ethnic region’ are more likely to collapse.

Further, there are several small ‘self-administered zones’. Some groups assert that these should be upgraded to full provinces (states). One, the Wa, have their own official currency and language (both Chinese), and the largest non-state army in the country. The Wa have not actively participated in the concurrent national ceasefire or constitutional reform processes, yet it is difficult to see how their demands could be resisted if peace is to be achieved.

The other major issue of debate on federalism pertains to the powers of the states and regions. In Nepal, the provinces have a rather broad set of powers and the potential to become strong in their own right. In Myanmar, states and regions have a very weak set of powers, including no law and order powers, and low revenue raising capacity. The debate over powers in Nepal has been relatively muted. No changes to the division of powers have been made across the various drafts of the constitution (Breen, 2018c, pp. 121-7).

Conversely, in Myanmar, the provincial boundaries are taken by many to be settled, so the next best design option to prevent secessionism (as perceived) is by not allowing the states and regions to assume the resources needed to mount a successful movement – in particular, law and order powers, and of course, a federal army[6] (Breen, 2018c, pp. 127-34). If the boundaries of the states and regions were changed (or de-ethnicised), perhaps a more balanced division of powers might be countenanced.

The role of the provinces in the governance of the centre (shared-rule) is subject to very little discussion. Bicameralism is accepted but mostly, a role (for ethnic minorities) in the centre is anticipated to come through their involvement in the major political parties, rather than as some part of grand coalition involving ethnic parties or provinces, or proportionality (Breen, 2018c, 158-66).

Conclusion

Nepal is currently implementing its new (2015) federal constitution. Myanmar has some way to go before it can be said to have federalism, however, there is a commitment, and many see it as inevitable. Further, there are important lessons and innovations that can be drawn from their process and their existing arrangements.

For one, I argue that there is a regional model emerging, which deserves more research and attention (Breen, 2018c, pp. 40-51). Secondly, other states in Asia continue to face the federal challenge. Sri Lanka (still) has a constitutional assembly in place, and there is a draft (quasi-federal) constitution being tossed around. The Philippines is also considering federal constitutional change. The president campaigned on a promise to establish federalism (and eliminate drugs) and a draft has been released to the public. Thirdly, Nepal successfully deployed a participatory process, while Myanmar’s is elite driven.

Finally, the secession risk is an issue that pervades federalism debates across the globe (see, Keil and Anderson, 2018: 96-99).[7] Yet, it has not been adequately assessed or understood – including how federal state-builders might best manage it. Irrespective of the normative understanding of secession one takes, there are few people involved in constitutional reform in Asia that would ever contemplate enabling secession or increasing the risk otherwise. So what are the best ways to manage secession risks? And can we better understand the health of a federal system by understanding how and why a secession risk fluctuates?

The design of holding-together federalism is about risk management, and for many, the biggest risk is secession. When the military in Myanmar becomes satisfied that federalism, in one way or another, will not lead to secession, then the next hurdle can be crossed. Such an understanding does not need to come via renunciation or by force, but through design.

Suggested Citation: Breen, M. G. 2019. ‘The Federalism Debates in Nepal and Myanmar: From Ethnic Conflict to Secession-risk Management’. 50 Shades of Federalism. Available at:

References

Breen, M. G. (2018a). Nepal, federalism and participatory constitution-making: Deliberative democracy and divided societies. Asian Journal of Political Science, 26(3), 410-430.

Breen, M. G. (2018b). The Origins of Holding-Together Federalism: Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 48(1), 26-50.

Breen, M. G. (2018c). The Road to Federalism in Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka: Finding the Middle Ground. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Devkota, K. (2012). A Perspective on the Maoist Movement in Nepal. Kathmandu: D.R. Khanal.

Erk, J., & Anderson, L. (2009). The Paradox of Federalism: Does Self-Rule Accommodate or Exacerbate Ethnic Divisions? Regional & Federal Studies, 19(2), 191.

Government of Nepal & Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). (2006). Comprehensive Peace Agreement. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

Hale, H. E. (2004). Divided We Stand: Institutional Sources of Ethnofederal State Survival and Collapse. World Politics, 156(2), 165-193.

International Crisis Group. (2016). Nepal’s Divisive New Constitution: An Existential Crisis. Brussels: International Crisis Group.

Keil, S. and Anderson, P. 2018. ‘Decentralization as a tool for conflict resolution’ in K. Detterbeck and E. Hepburn (eds), Handbook of Territorial Politics. Cheltenham: Edard Elgins, PP. 89-108.

Lawoti, M. (2014). Reform and Resistance in Nepal. Journal of Democracy, 25(2), 131-145.

Sanjaume, M. (2018). ‘Secession and Federalism: A Chiaroscuro’, 50 Shades of Federalsim. Available at: http://50shadesoffederalism.com/diversity-management/secession-federalism-chiaroscuro/

Walton, M. J. (2008). Ethnicity, Conflict, and History in Burma: The Myths of Panglong. Asian Survey, 48(6), 889-910.

Williams, D. C. (2017). A Second Panglong Agreement: Burmese Federalism for the Twenty-first Century. In A. Harding & K. K. Oo (Eds.), Constitutionalism and Legal Change in Myanmar (pp. 47-69). Oxford & London: Hart Publishing.

Further reading

Breen, M. G. (2018). The Road to Federalism in Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka: Finding the Middle Ground. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Harding, A., & Oo, K. K. (Eds.). (2017). Constitutionalism and Legal Change in Myanmar. Oxford and London: Hart Publishing.

Karki, B., & Edrisinha R. (Eds.) (2014). The Federalism Debate in Nepal: Post Peace Agreement Constitution Making in Nepal (Vol. II). Kathmandu: United Nations Development Programme Support to Participatory Constitution Building Nepal.

[1] In the case of Nepal, the conflict was between the state and a Maoist insurgency. However, in Nepal class and ethnicity align and the Maoists deliberately and explicitly incorporated and pursued the demands of the non-dominant ethnic groups (Devkota, 2012).

[2] That federalism can simultaneously accommodate and exacerbate ethnic difference.

[3] Known as states and regions in Myanmar.

[4] The constitution’s amendment process requires the approval of more than 75% of all representatives in the national parliament, thus giving the military an unofficial veto.

[5] Around half the population of Nepal lives in the Terai and, at the time, armed groups with links to India were running rampant.

[6] A federal army is demanded by EAOs to accord them recognition and to prevent a future military coup.

[7] See also, Sanjaume (2018) ‘Secession and Federalism: A Chiaroscuro’ http://50shadesoffederalism.com/diversity-management/secession-federalism-chiaroscuro/

Dr Michael Breen is a McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at The University of Melbourne. Michael’s research focuses on ethnic conflict, federalism and constitution-making in Asia, and deliberative constitutionalism.

Dr Michael Breen is a McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at The University of Melbourne. Michael’s research focuses on ethnic conflict, federalism and constitution-making in Asia, and deliberative constitutionalism.