Abstract

Among international rankings, Austria is often considered as a rather centralized country given that the Federal Constitution does not offer many legislative competences for the Länder (federal units). After an overview of key features of Austrian federalism as laid down in the Federal Constitution, this entry seeks to compare demographic facts of Austrian federalism with those of decentralized unitary systems. Further, recent issues of the country’s political discourse are outlined.

Introduction

If one compares the Austrian Federation with other federal systems, one will quickly realise that it is a relatively small country. Anyone who compares this Federation with unitary systems will recognise that there are larger countries that are far more centralised than Austria.

Thus, the domestic discussion often concludes that Austria – if compared to other countries – affords a federalism that suffers from particularly small-scale structures.

When comparing state structures, one must be careful to not compare certain basic data such as population, area, and number of administrative subdivisions at random. This is to say that the data do not prejudice the competences of federal units, the regions of a decentralised unitary state, or simply an administrative unit. The very nature of subnational entities does not fully determine or clarify their structures. For example, not only the Austrian states – according to Art. 2 of the Austrian Federal Constitution (B-VG = Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz) the “Länder” – have parliaments (the Landtage), but so do certain regions of unitary states. These regional parliaments might have parliaments with stronger competences than those of the Austrian Landtage.

Basic Structures of Austrian Federalism

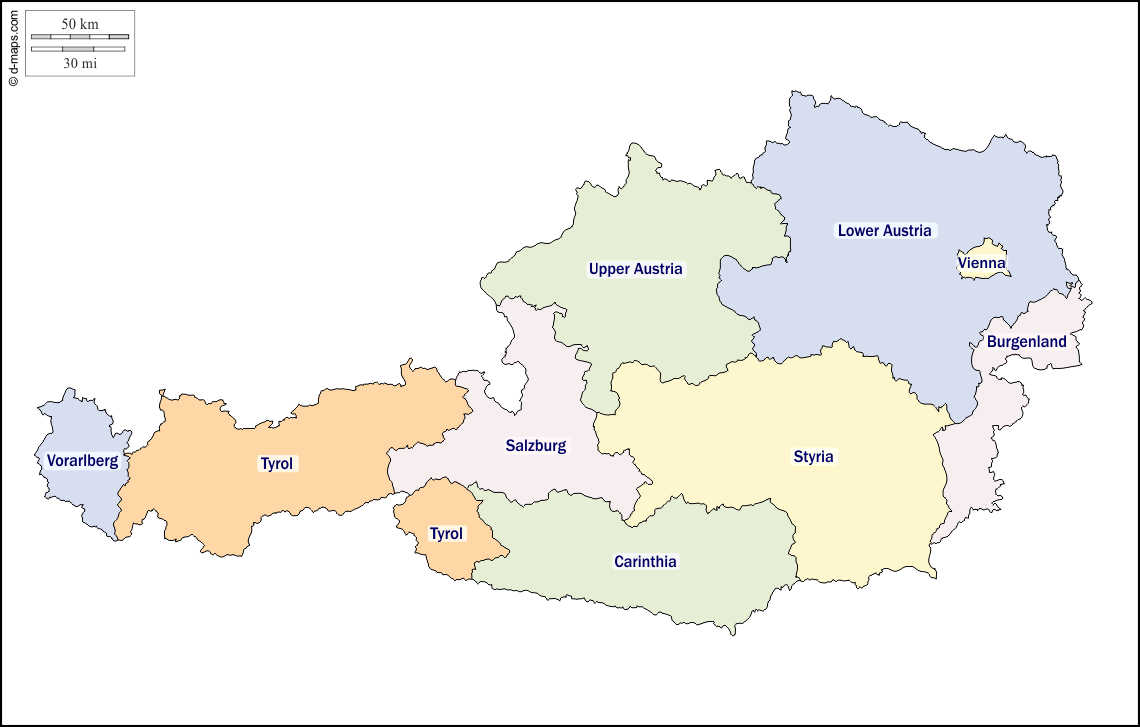

The Federal Republic of Austria was created in 1920 and can thus be ranked among the “old “European federal systems. After the breakdown of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918, the “Länder” and former “crownlands” played an important role in building the new Republic. At that time, seven of today‘s nine Länder, which are mentioned in Art. 2 of the Austrian Federal Constitution (hereinafter “B-VG”), were surviving entities of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. The Burgenland was part of Hungary and joined Austria in 1921. The capital Vienna was part of Lower Austria and became a Land of its own in 1922.

Initially, the role of the Länder in the process of drafting the new constitution was comparatively strong because the new Republic needed the former crown-lands to establish a stable government. As time went by, the federal government could consolidate its power and the political influence of the Länder decreased. As the B-VG was adopted in 1920, it was based on a compromise between the Social Democrats (hereinafter “SPÖ”) and the Christian-Social-Party (hereinafter “ÖVP”). While the former preferred a strong unitary state, the latter supported the formation of a federation similar to Switzerland. These entirely different attitudes towards federalism resulted in the Austrian Federation. Because of this fact, the constitution was marked from the very beginning by strong unitary elements and a clear power imbalance in favor of the federal government.

Since the formation of the Austrian Federation, the B-VG has been amended many times. The majority of these amendments have further accentuated the unitary tendency enshrined in the constitution by transferring additional powers to the federal level. This approach also applies to the two amendment acts of 1925 and 1929, especially regarding the issue-areas of “security administration” and “police organization”. Moreover, the amendment of 1925 is of particular importance because it has brought the distribution of competences into force with effect from 1 October 1925 onwards.

Art. 2 B-VG explicitly stipulates that Austria is a federal state which consists of nine autonomous Länder, namely Burgenland, Carinthia, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tyrol, Vorarlberg, and Vienna. The prevailing doctrine regards Art. 2 B-VG as a provision with solely programmatic character. However, federalism is classified as one of the basic principles of the B-VG besides the democratic principle, the republican principle, the liberal principle, the principle of the rule of law and the principle of separation of powers. According to Art. 44 para 3 B-VG, an abolishment or a considerable modification of one of these basic principles is considered as a total revision of the constitution and, therefore, needs to be approved by a referendum.

According to the jurisdiction of the Federal Constitutional Court, the content of the federal principle arises from at least four substantive elements: The distribution of legislative and administrative competences, the participation of the Länder in federal legislation, the constitutional autonomy of the Länder and the participation of the Länder in the federal administration. However, federal theory suggests that there has to be one additional element, namely the autonomy of the Länder in budgeting and spending.

The distribution of competences is entrenched in Art. 10 – 15 B-VG. These Articles differentiate between four types of distribution of legislative and executive powers: Exclusive federal legislation and execution (Art. 10 B-VG); federal legislation executed by the Länder (Art. 11 B-VG); framework legislation by the federation which is implemented and executed by the Länder (Art.12 B-VG); exclusive Länder legislation and execution (Art. 15 B-VG). The latter is designed as residual competence, which means that the Länder are responsible for all matters which have not been enumerated explicitly in favor of the federation. Certainly, the clear majority of competencies can be found in Art. 10 B-VG. This provision contains fundamental competencies such as the Federal Constitution, external affairs, civil law affairs, matters of trade and industry, labor legislation and public health with certain exceptions. The Länder remain competent, among others, for the subject-areas of building, nature protection and regional planning.

According to Art.13 para 1 B-VG, the competences of the Federation and the Länder in the field of taxation are regulated in a separate federal constitutional act, namely the Financial Constitutional Act of 1948. This act defines abstract types of taxes and enshrines the competence of the federal legislator to decide about the distribution of tax-raising powers which in turn is incorporated into the Financial Adjustment Act (“Finanzausgleichsgesetz”). The latter is in practice negotiated between the Federation, the Länder and the municipalities. Against this background, the distribution of competences regarding finances is shaped in an eminently centralistic way. The Länder have almost no genuine tax income. Similar to the finance sector, competences regarding schools and education are regulated separately in Art. 14 and 14(a) B-VG.

The Federal Council is the most important legally provided instrument of the Länder to participate in federal legislation. Even though its role as the representative of the interests of the Länder at the level of federal legislation is not explicitly stated in the B-VG, the organization and functions of the Federal Council indicate this rationale. The relevant provisions regarding the organization of the Federal Council can be found in Art. 34- 37 B-VG. The representatives of the Federal Council are elected by the parliament of each Land. According to Art. 34 para 1 B-VG, the Länder are represented in the Federal Council in proportion to the population of each Land.

Generally speaking, Austria’s Federal Council is characterized as weak. This assessment can be rooted within the few functions of this institution (constitutional weakness) as well as within the fact that the Federal Council rarely uses existing functions (political weakness). According to Art. 42 B-VG the Federal Council may veto a bill by the National Council. However, the National Council can override this veto by a repeating vote on the bill. Besides this option to suspend the federal legislation, an absolute veto is granted to the Federal Council for a limited number of cases. The most prominent example is Art. 44 para 2 B-VG. This provision is of particular importance for the federal system because it enshrines an absolute veto in cases when constitutional laws or constitutional provisions contained in simple laws restrict the Länder’s competencies in legislation or execution.

In addition to the Federal Council and its functions, the Länder may participate on federal legislation in form of the rights of consent to several laws (Art. 3 para 2, 14b para 4, 94 para 2, 102 para 1 and 4, 131 para 4 and 135 para 4 B-VG).

According to Art. 99 para 1 B-VG and respective judgments of the Constitutional Court subnational constitutions must not contradict the Federal Constitution. This implies that the constitutions of the Länder may codify anything insofar as they do not contradict federal constitutional law.

The so-called “indirect federal administration” constitutes a further substantive element of the federal principle. This form is characterized by the Länder’s execution of federal affairs even though they remain a matter of federal competence. The competent authorities are the Land Governors who must follow, in their role as indirect federal administrators, the directives of the respective federal minister. Art. 102 para 1 B-VG stipulates indirect federal administration as a general rule. However, Art. 102 para 2 B-VG contains an extensive catalogue of exceptions that can be directly executed by federal authorities. The fact, that the federation makes use of these far-reaching exceptions has led to the view that the principle of indirect federal administration became relativized.

In general, formal and informal cooperation plays an important role in Austrian federalism. In particular, this applies to agreements concluded according to Art. 15(a) B-VG; these agreements might be the most far-reaching instruments of cooperative federalism in Austria. These agreements may be concluded either between the Länder or between the Federation and all or only selected Länder as far as the respective competencies are concerned. However, they require an act of implementation by the respective legislative or executive bodies. Furthermore, contracts between the Federation and the Länder may be based on private law as Art. 17 B-VG determines that the distribution of competences does not affect the ability of the federation and the Länder to act under private law.

Informal cooperation works along with the Conference of Land Governors (“Landeshauptleutekonferenz”). This horizontal model of cooperation functions as a relatively efficient counterbalance to the weight of the federal order of government. Indeed, despite a continuous process of centralization of legislative powers, the Conference of the Land Governors has developed into an important platform of the Länder, especially concerning financial equalization and negotiations in respect of cost-sharing for the execution of federal law by the Länder and municipalities.

Comparison of Federal and other Decentralized Systems

Besides the simple dichotomy of unitary states and federal states, there are many gradations in between. The best examples thereto are unitary states with asymmetrical regional autonomies such as in the UK, Denmark, Finland or Portugal. Equally, the sub-division of federal states is illustrative of the federal scale. Previous years have demonstrated that federalization often followed preceding conflicts.

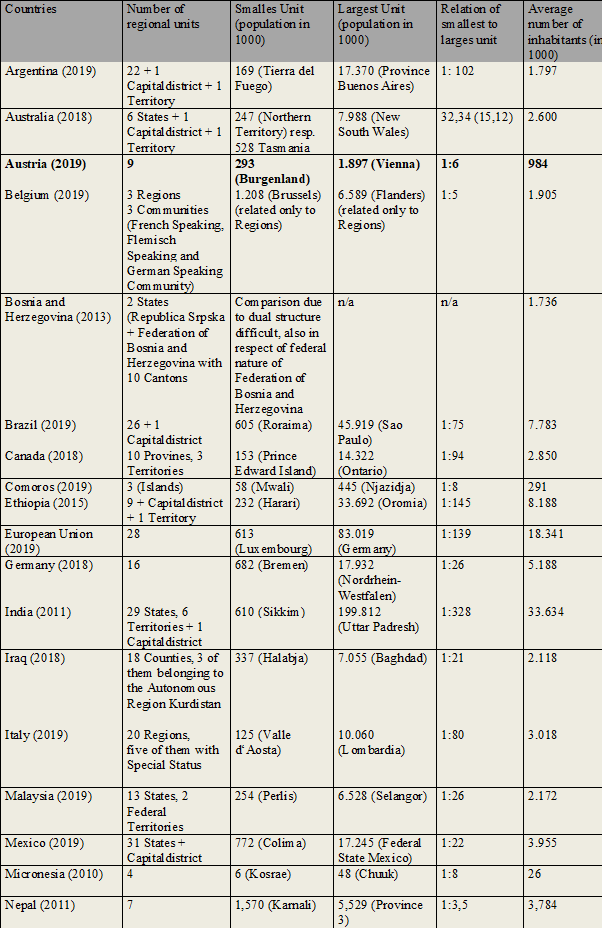

The diversity of federal systems is enormous. Practically, there is no uniform size of regional units. There are numerous Swiss cantons which are smaller than the smallest Austrian Land in terms of population. The same applies to Canada (Prince Edward Island) or Belgium (German-speaking Community). The following tables show the differences:

A Comparison of Parliaments: How Many Politicians Does a State Need?

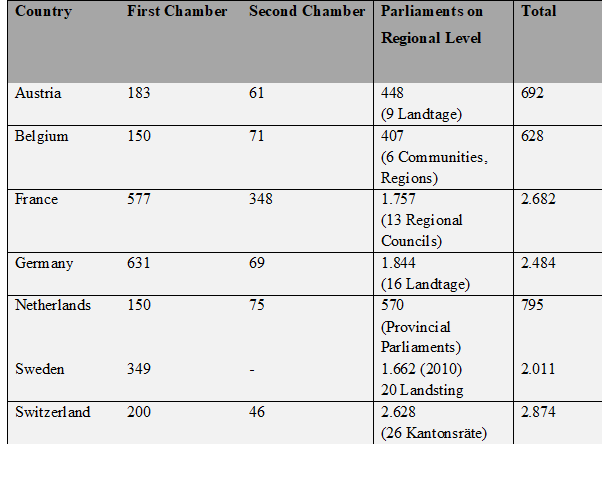

According to public sentiments, Austria affords itself “too many” politicians because of its federal system. This argument is fundamentally opposed by the fact that it is advantageous from a democratic point of view if as few people as possible are “represented” by a member of parliament. The small ratio is said to improve the connection between representatives and those being represented. Moreover, the discussion on a reduction in the number of politicians ultimately leads to a devaluation of politics.

International comparison shows that Austria does not stand out from the crowd about the number of officials at the federal and regional levels. This finding holds for federal countries (Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland), as well as for decentralized unitary states (France, the Netherlands, Sweden).

Conclusions

The nine Austrian Länder are comparatively small, but in international comparison, they can compete with comparably smaller regional units of legislative sovereignty in – exemplarily – Switzerland and Belgium. To indicate this comparison: the smallest Swiss Canton – Appenzell-Innerrhoden, with about 15,000 inhabitants, is much smaller than the Burgenland, Austria’s smallest federal state (about 290,000 inhabitants). A similar finding applies to the German-speaking Community of Belgium with about 70,000 inhabitants. In the context of the European Union, it should also be pointed out that the Finish Aland Islands, for example, with about 30,000 inhabitants, also have their legislative sovereignty.

By international comparison, the disparities between the individual member states of federal systems are striking. In this respect, the differences between the Austrian Länder are comparatively small.

Even decentralised unit states have regional structures that are comparable with those of the Austrian Länder (e.g. France, the Netherlands, Sweden). Parliamentary assemblies comparable to the Austrian provincial parliaments are also attributed to these decentralized units. The core difference lies within the fact the Austrian Landtage are bestowed with more (legislative) competences and thus enjoy a greater room for manoeuvre.

The “density of politicians” in Austria at the federal/state level is by no means unusual. Both, federal states with similar size as Austria (Belgium, Switzerland) and unitary states have comparable numbers of politicians (Netherlands, France). Others (such as Sweden) might even enjoy larger numbers of political functionaries.

Suggested Citation: Bußjäger, P and Johler, M. 2020. ‘The Austrian Federation in Comparison‘. 50 Shades of Federalism. Available at:

Further Reading

Bussjaeger, P. (2017). The new Austrian Administrative Court System: From 121 to 12. A Review of an Ambitious Reform. In: Studi parlamentari e di politica costituzionale 195 (196), pp. 83 – 98.

Bussjaeger, P., Johler, M. (2018). Distribution of Powers in Federal Systems. Max Planck Encyclopedia of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Bussjaeger, P., Johler, M., Schramek, Ch. (2018). Federalism and Recent Political Dynamics in Austria, in. Revista d’estudis autonòmics i federals, [en línia], 2018, Núm. 28, p. 74-100, https://www.raco.cat/index.php/REAF/article/view/349237 [Consulta: 21-04-2020].

Gamper, A. (2010). Intergouvernementale Gesetzgebung. In: P. Bussjaeger, ed, Kooperativer Föderalismus in Österreich. Beiträge zur Verflechtung von Bund und Ländern, Vienna/Innsbruck: Braumüller, pp. 26-47.

Karlhofer, Ferdinand/Pallaver, Günther (2013). Strength through Weakness. State Executive Power and Federal Reform in Austria, Swiss Political Science Review 19 (4), pp. 41-59.

Pernthaler, P. (2004). Österreichisches Bundesstaatsrecht. Vienna: Verlag Österreich.