Abstract

With Brexit looming, the United Kingdom is undergoing a constitutional crisis. The adaptation of the devolution process, initiated the late 1990s, to the withdrawal from the European Union and the autonomy of Scotland in particular are some of the central issues at stake. Just a few years after the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, this crisis highlights some of the limits of this process as well as Scotland’s vulnerabilities. These are of three orders: fiscal, commercial, and constitutional. This short article describes them.

Introduction: From “Independence in Europe” to Brexit

As demonstrated by the successive reforms of the Scottish devolution settlement over the last twenty years or so, the “Scottish question” mainly comes down to Scotland’s economic autonomy as part of the United Kingdom (Gibb et al. 2017; Keating 2017; McHarg et al. 2016; Rioux 2016). Yet, most of the crucial issues associated with devolution or independence will now have to be revisited based on the results of current negotiations over Brexit (Hassan and Gunson 2017). To get a good grasp of the challenges now facing Scotland therefore, one must consider both the devolution process as it unfolded since 1998, and the potential consequences Brexit could entail for it. Scotland’s fiscal autonomy in the United Kingdom (UK), as well as its prerogatives in European and commercial matters, are thus central concerns.

Scotland in the UK

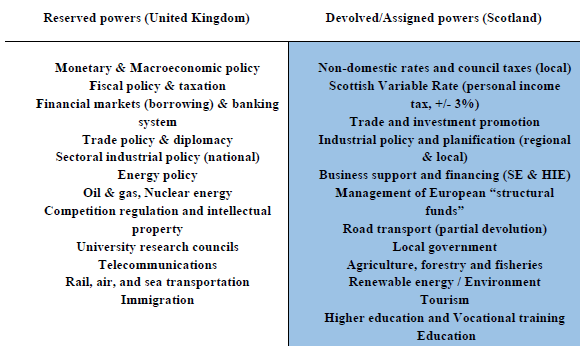

Economic powers transferred to Scotland in the wake of parliamentary devolution in 1998-1999 were substantial, but most fiscal, financial, macroeconomic and commercial powers were “reserved” to the UK (Keating 2010; Figure 1). While substantially increasing Scottish autonomy, the Scotland Act 1998 thus led to various imbalances. On the one hand, devolution bestowed Scotland significant autonomy in terms of public spending: the share of total public expenditures in Scotland emanating from the Scottish Executive, Scottish local authorities, or Scottish public enterprises and quangos reached 55% as early as 1998-1999. Although transferring important budgetary responsibilities to Scotland however, devolution maintained it in a position of fiscal subordination: until the reforms initiated by the Scotland Act 2012 and Scotland Act 2016 took effect, over 90% of Scottish budgets remained composed of transfers from the UK government.

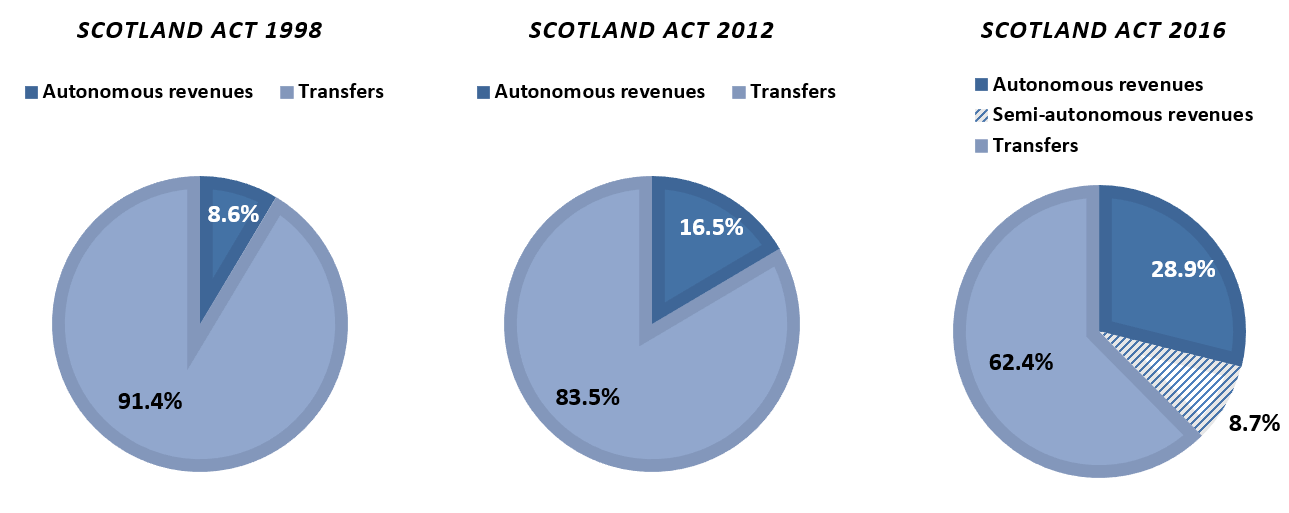

This lack of fiscal autonomy had major repercussions. Scotland found itself unable to elaborate targeted fiscal incentives for instance, as corporate taxes remained under British control. Neither did the Scotland Act 1998 grant Scotland autonomous borrowing powers, despite the fact that Scotland henceforth became solely responsible for large swaths of industrial, environmental, and transport policy. Scotland was thus placed in a paradoxical position: as devolved spending powers were multiplied – economic development, education, healthcare, public safety, culture, etc. – taxes controlled by the Scottish Executive (i.e. its “devolved revenues”) only represented, on average, 12% of its “devolved expenditures” under the Scotland Act 1998 (Figure 3). Such an imbalance between spending autonomy (expenditure) and fiscal autonomy (revenue) is, according to mainstream theories of fiscal federalism, unsound given that fiscal decentralization should accompany expenditure decentralization – “finance should follow function” (Rodden 2006; Shah 2007).

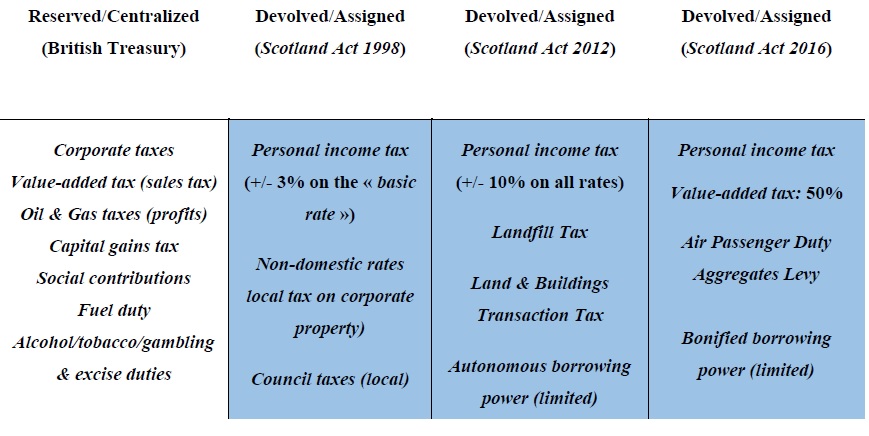

Figure 1. Distribution of economic and fiscal powers, Scotland Act 1998

Scottish National Party victories in the 2007 and 2011 Scottish elections then led, notably for these reasons, to a few reforms: ten personal income tax points, as well as a couple of minor taxes were first devolved by the Scotland Act 2012, which also granted Scotland limited autonomous borrowing powers. Yet this reform, of which most dispositions came into force in 2015-2016, only brought Scotland’s “devolved revenues” up to a little more than 16% of its total revenues (Figure 2), and thereby the share of devolved Scottish expenditures covered by devolved revenues to around 22% (Figure 3).

Figure 2. The evolving distribution of fiscal powers since 1998 and the corresponding fiscal autonomy of Scotland

The Scotland Act 2016 beget more substantive reforms, many of which, however, have yet to be operationalized. New powers over social security will notably be transferred to Scotland, increasing the share of devolved expenditures to 62% of total Scottish public spending (Figure 3). Furthermore, new fiscal powers were partially or wholly devolved which will raise Scotland’s “autonomous” (devolved) and “semi-autonomous” (assigned) revenues to 37% of its total revenues (Figure 2), and to 48% of its devolved expenditures (Figure 3). Corporate taxes, social contributions of employers and capital gains taxes, however, were reserved by the British Government. Their persisting centralization is particularly problematic considering that by themselves, social contributions and corporate taxes represent almost a quarter of Scotland’s onshore tax revenues. Besides, taxation of offshore oil & gas revenues remain a prerogative of the UK government. In 2008-2009, back when the barrel of Brent crude oil reached a value of over $100 US, these taxes represented more than 20% of total fiscal revenues generated in Scotland. The issue of their control, thus, endures as a major constitutional stumbling block.

On the other hand, Scotland acquired almost complete control over personal income taxes, the revenues of which account for over a fifth of its total tax revenues, and was assigned half of the British sales tax (VAT) Scottish revenues. Aside from social contributions, revenues from the sales tax are the only ones that have grown, in the UK as in Scotland, in proportion of total fiscal revenues since the late-1990s. Consequently, this assignment of half of the VAT revenues to Scotland will represent a major step forward. Moreover, Brexit could theoretically allow for its full devolution to Scotland by releasing the UK from the European policy of uniform domestic VAT rates. A new model combining Scottish and British sales taxes in Scotland, each with a distinct rate, could then be conceivable. Scotland, however, still lacks control over any significant corporate tax, and its powers over personal income and indirect taxation have not allowed it to end its reliance on budget transfers from the UK, or its subordination to British fiscal policies.

Figure 3. The evolution of Scotland’s average spending (expenditures) and fiscal (revenues) autonomy

Scotland in the World

Just as much as this issue of fiscal autonomy, matters related to the commercial risks associated with secession and to the European status of an independent Scotland were central in 2014. The Brexit vote, however, raised even more fundamental questions of the symmetry of Scottish and British commercial interests, and of the advantages and disadvantages of EU membership for a post-Brexit, independent Scotland. Even though the importance given to commercial considerations largely preceded devolution, the transfer of trade and investment promotion responsibilities to Scotland accentuated this feature. Scotland’s commercial paradiplomacy is therefore very dynamic, and is deployed through a network of international representations financed and managed jointly by the Scottish Government and Scottish Development International, a subsidiary of the public agencies Scottish Enterprise and Highlands & Islands Enterprise.

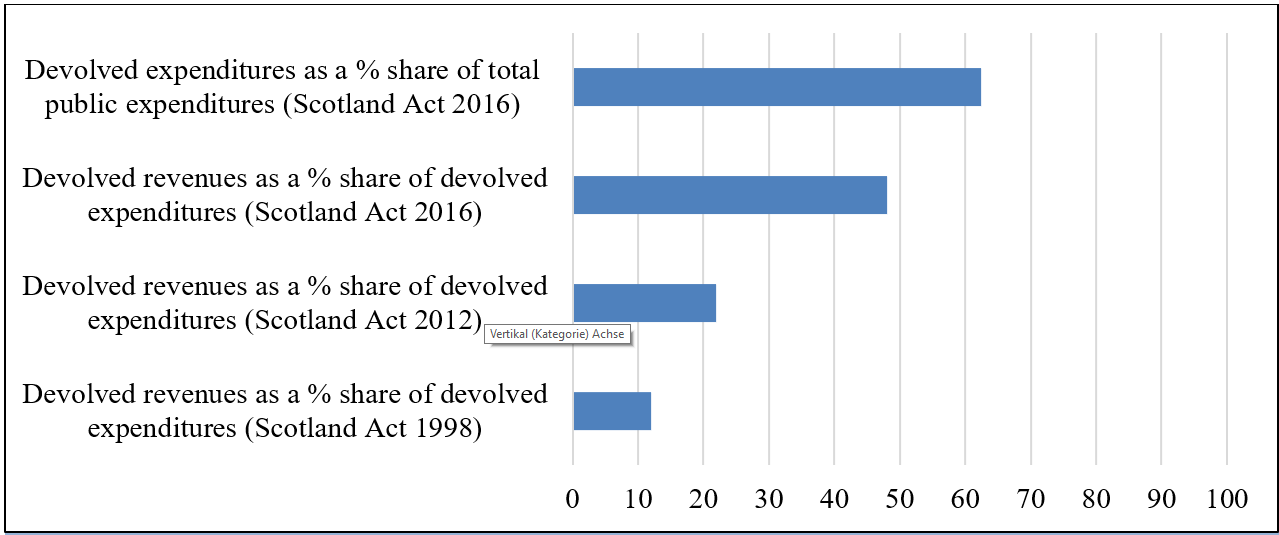

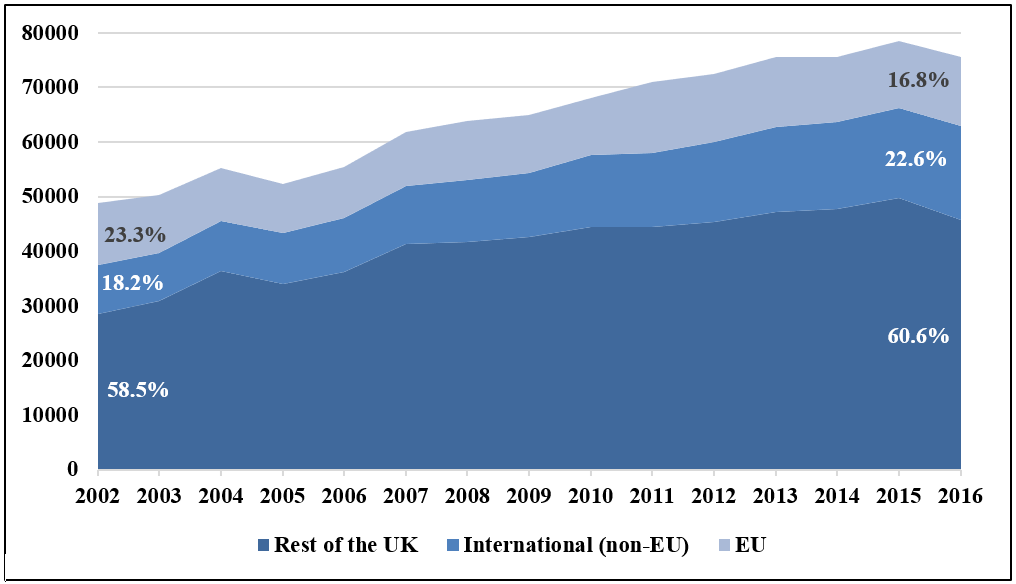

The Scottish Government’s active stance in these matters reflects a desire for the diversification of Scotland’s trade partners, as already by the turn of the 2000s, Scottish exporters were highly dependent upon British markets (Figure 4). This imbalance only widened further in the following years, so that by 2016 British markets monopolized over 60% of Scottish exports against only 39.4% for EU (16.8%) and other international markets (22.6%). Still, EU membership entailed important advantages: it allowed Scotland to attract more foreign investment, and helped it diversify its export markets through the various trade deals contracted between the EU and Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, Israel, South Korea, Mexico, South Africa, Japan and Canada, notably.

Figure 4. The evolution of Scottish exports (goods & services) by destination

(£ millions and % of total exports)

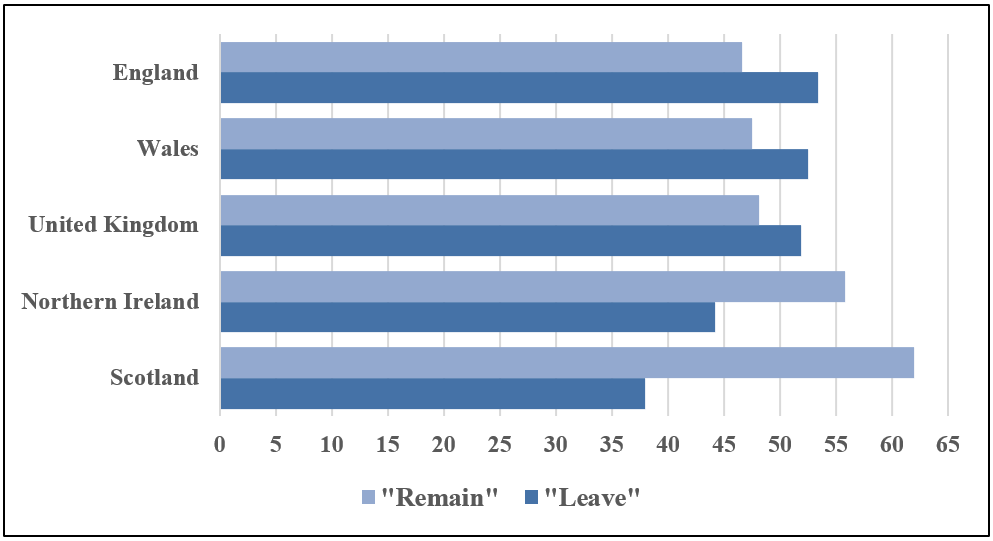

This is why, until the adoption, in June 2015, of the EU Referendum Act which established the terms of the Brexit referendum, the Scottish Government tried to amend it by imposing a “double majority lock” requiring a majority of votes not only at the British level by also within each nation constitutive of the UK for a result favorable to Brexit to be considered binding (Scott 2016: 191-192). This was in vain: despite the Scottish (62%) and Northern Irish (55.8%) majorities in favor of the option to remain part of the EU, the slight Welsh (52.5%) and English (53.4%) majorities in favor of Brexit were sufficient (Figure 5).

This Brexit vote still fundamentally altered the terms of the constitutional debate in Scotland for a simple reason: if, at over 8%, exports to the EU represent an important part of Scotland’s GDP, exports to the rest of the UK represent over 30% of its GDP. Jeopardizing a part of the latter in order to safeguard the former, as might happen in the case of a post-Brexit secession of Scotland followed by EU membership, would thus be an important risk. This is especially true given the fact that the EU has been attracting a decreasing share of Scotland’s international exports (Figure 4).

Scotland, besides, has no voice of its own – if only through the UK’s Joint Ministerial Committee – in negotiations with the EU over Brexit, and will have no veto power over their results either. Faced with the possibility of a “no deal” Brexit or, at best, of a simple free trade deal limited to goods and excluding the UK from both the EU Customs Union and Single Market, the Scottish Government first pleaded, for a time, in favor of an asymmetric arrangement allowing Scotland to become an “associate” or a full member of the European Free Trade Association and European Economic Area. There are some precedents in that regard: Greenland and the Faroe Islands are members of neither the EU nor the European Economic Area, unlike Denmark; the Channel Islands have access to the European Single Market and are part of the Customs Union without being members of the EU; and the archipelago of Svalbard is excluded from the European Economic Area even though Norway is a member (Lock 2017).

Figure 5. Brexit vote in the UK and constitutive nations (%)

Such an asymmetric settlement remains improbable in the case of Scotland, however. This would necessitate difficult negotiations with the UK and EU, as well as complex institutional dispositions. It would also introduce certain trade barriers between Scotland and the rest of the UK. Finally, such a settlement would require the devolution of various new powers to Scotland, notably on matters of economic regulation, energy, financial markets, international representation, social security, immigration, and training (Scottish Government 2016: 41-43; Lock 2017). Most likely doomed to fail, references to this strategy were thus practically abandoned in Scottish Government’s most recent analysis document on Brexit (Scottish Government 2018).

The British Government, indeed, has seemingly been adopting a centralizing stance on Brexit so far. A first good example is the Trade Bill, that aims to insure maximum continuity, after Brexit, with regards to the commercial relationships linking the UK and countries with which the EU (and therefore the UK as a member State) shares trade agreements. This Bill, denounced by the Scottish Government for its centralizing tendencies, establishes that Scotland would essentially inherit, on matters of trade policy, only the obligation to implement and enforce, within its own fields of jurisdiction, the dispositions of future trade agreements negotiated by the British Government (Melo Araujo 2017). The European Union (Withdrawal) Act is another telling example: adopted in June 2018 and designed to convert European laws and regulations into British versions after Brexit, this Act provides that, even in cases where devolved Scottish jurisdictions are clearly affected – such as in agri-food and environmental matters, notably – these powers should first be repatriated to London before negotiations can be launched with regional authorities regarding their partial devolution (HM Government 2017: 10).

The Scottish Parliament, consequently, refused to give its consent to this Act as is “normally” required by virtue of the Sewel Convention given that it affects Scotland’s devolved responsibilities. Yet, not only can Brexit be characterized as a set of “extraordinary” circumstances and thus exempted from the Sewel Convention, but strictly speaking this Convention does not grant Scotland a veto over British legislation anyway. Faced with this predictable stalemate, the Scottish Government adopted its own UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Legal Continuity) (Scotland) Bill in March 2018, which stipulates for its part that the Scottish Parliament should inherit, automatically and exclusively, responsibility for any current European (or shared) power which, in accordance with the Scotland Act 1998 and its subsequent reforms, relates to devolved Scottish jurisdictions. At the time of writing, this Bill was however still on hold as the Supreme Court of the UK was asked to rule on its constitutionality.

Conclusions

More than twenty years after devolution, Scotland thus finds herself in a position of triple vulnerability: fiscal, commercial, and constitutional. Scotland is fiscally vulnerable, first, because well over half of its budget revenues are composed of British transfers over which it only exerts limited control and influence. Second, Scotland is also commercially vulnerable, given that it is highly dependent on British markets and policies for its exports, and that this is likely to worsen in the wake of Brexit. Finally, Scotland is constitutionally vulnerable for the autonomous exercise of its own responsibilities, in devolved areas of jurisdiction, is now being restricted and, in some cases, even challenged.

Bibliography and Complementary Reading

Gibb, Kenneth, Duncan Maclennan, Des McNulty and Michael Comerford (eds.) (2017), The Scottish Economy: A Living Book. New-York: Routledge.

Hassan, Gerry and Russell Gunson (eds.) (2017), Scotland, the UK and Brexit : A Guide to the Future. Edinburgh: Luath Press Limited.

HM Government (2018), The Future Relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union. London.

– (2017), Legislating for the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union. London.

Hughes, Kirsty (2016), “Scotland’s Choice : Brexit with the UK, Independence, or a Special Deal,” Friends of Europe, Discussion Paper, Center on Constitutional Change.

Keating, Michael (ed.) (2017), Debating Scotland. Issues of Independence and Union in the 2014 Referendum. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keating, Michael (2010), The Government of Scotland: Public Policy Making after Devolution. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Lock, Tobias (2017), “A Differentiated Brexit for Scotland?,” in G. Hassan and R. Gunson (eds.), Scotland, the UK and Brexit : A Guide to the Future. Edinburgh: Luath Press Limited, Chapter 2.

McHarg, Aileen, Tom Mullen, Alan Page and Neil Walker (eds.) (2016), The Scottish Independence Referendum: Constitutional and Political Implications. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Melo Araujo, B. (2017), “UK Post-Brexit Trade Agreements and Devolution,” CETLS Working Paper Series, Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast.

Rioux, X.H. (2016), “Peut-on faire l’économie de l’autodétermination? Le cas écossais,” in M. Seymour (ed.), Repenser l’autodétermination interne. Montreal: Éditions Thémis, pp. 175-196.

Rodden, Jonathan A. (2006), Hamilton’s Paradox : the Promise and Peril of Fiscal Federalism. New-York: Cambridge University Press.

Scott, Sionaidh Douglas (2016), “Scotland, Secession and the European Union,” in A. McHarg, Aileen, T. Mullen, A. Page and N. Walker (eds.), The Scottish Independence Referendum: Constitutional and Political Implications. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 8.

Scottish Government (2018), Scotland’s Place in Europe: People, Jobs and Investment, Edinburgh.

– (2018b), Export Statistics Scotland 2016. Edinburgh.

– (2017), Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland 2017-18. Edinburgh.

– (2016), Scotland’s Place in Europe. Edinburgh.

Scottish Policy Foundation (2018), Scotland’s Tax Powers. Edinburgh.

Shah, Anwar (ed.) (2007), A Global Dialogue on Federalism. The Practice of Fiscal Federalism : Comparative Perspectives. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

X. Hubert Rioux is a Banting Postdoctoral Fellow (SSHRC) at the École nationale d’administration publique in Montreal, Quebec. His current research focuses on economic nationalism, commercial paradiplomacy, fiscal federalism, economic development and state corporations in Quebec, Scotland, and in a comparative perspective. He holds a Ph.D. in political science (comparative public policy) from McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario), where he completed a thesis on the development of corporate financing and venture capital ecosystems in Quebec and Scotland. Dr. Rioux also sits on the Board of the Canadian section of the International Center of Research and Information on the Public, Social and Cooperative Economy (CIRIEC).

X. Hubert Rioux is a Banting Postdoctoral Fellow (SSHRC) at the École nationale d’administration publique in Montreal, Quebec. His current research focuses on economic nationalism, commercial paradiplomacy, fiscal federalism, economic development and state corporations in Quebec, Scotland, and in a comparative perspective. He holds a Ph.D. in political science (comparative public policy) from McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario), where he completed a thesis on the development of corporate financing and venture capital ecosystems in Quebec and Scotland. Dr. Rioux also sits on the Board of the Canadian section of the International Center of Research and Information on the Public, Social and Cooperative Economy (CIRIEC).