Abstract

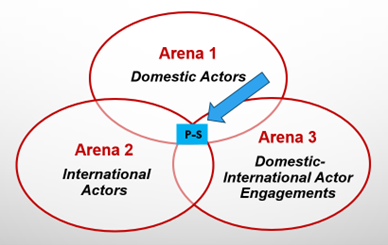

Power-sharing systems are complex, both in their design and daily operation. While the multifaceted nature of power-sharing is generally accepted by scholars and policymakers alike, understandings of the conditions under which these systems come into being, and how these conditions affect the implementation and the functioning of the power-sharing system, remain underdeveloped. Providing evidence from Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, this contribution sheds new light on what it takes to get to a power-sharing agreement. We argue that power-sharing as a solution to violent conflict is only adopted when there is convergence on this approach within three distinct arenas: among domestic actors; among international actors; and between invested international actors and their domestic clients. Whereas Lebanon represents a case where alignment existed across all three arenas and Iraq showcases a lack of convergence at the domestic level, Syria provides an important case in which these three arenas do not converge – thereby explaining why no agreement on power-sharing has been reached so far.

Under What Conditions Does Power-Sharing Come Into Being?[1]

There has been a growing recognition in the academic literature on power-sharing that we need to understand more about the conditions under which power-sharing systems come into being (McCulloch and McEvoy 2020; McGarry 2017; McEvoy and Aboultaif 2022; Aboultaif 2019). This is a timely and pressing question, with most contemporary examples of power-sharing, emerging out of peace processes at the end of violent conflict. Understanding how power-sharing is framed during cease-fire and peace negotiations, at what stage of the process it is introduced, and what role domestic actors and international mediators might play in post-conflict governance are all important areas for academic research. Likewise, policymakers tend to suggest power-sharing solutions where different groups are in conflict with each other, and where a military solution seems either unlikely or only possible with a substantial death toll and dangers of wider conflict escalation (Sisk 1996).

With funding from the Swiss Network for International Studies, the collaborative project “Power-sharing for Peace? Between Adoptability and Durability in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq” conducted over 50 interviews with international mediators, academics, political activists and local elites who have closely followed or participated in the negotiation, adoption and/or the implementation processes. We also organized 15 focus groups with participants from different segments of society to discuss the challenges of power-sharing adoption, implementation and performance. The results of this research indicate clearly that power-sharing systems only come into being when three conditions are met:

- when domestic conflict factions come to see power-sharing as the way to solve collective disputes,

- when there is support and agreement among international actors for a power-sharing solution, and

- when key international actors reinforce the commitment to power-sharing with their domestic proxies.

Whereas Lebanon’s Taif Agreement represents a case where alignment across these three arenas was possible, and Iraq showcases a lack of convergence at the domestic level but strong support from international actors, Syria is an important counter-factual case, in which no power-sharing system has been agreed upon, despite negotiations on a power-sharing solution since the outbreak of violence in 2011.

A New Model of Power-Sharing Adoption?

It is a truism that power-sharing adoption first requires consent by domestic elites. We refer to this as Arena 1. This arena is important to making a settlement work as it is the actors in this arena who are, after all, the ones who must agree to share power with one another. Imposed solutions, such as Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Dayton Peace Agreement, have proven highly unstable in practice, perpetuating a continuation of war-rhetoric and a discourse of politics as a zero-sum game. Bringing domestic elites together and encouraging power-sharing as an alternative to the continuation of conflict is therefore a fundamental element of any power-sharing solution. Elite consensus comes not by itself, but is often influenced by developments on the battlefields, external pressure, shifting demographic patterns or economic incentives (McGarry 2017). In two of our cases – Lebanon and Iraq – domestic consensus on power-sharing, in whole or in part, was an important element that paved the way to a more permanent political settlement. In Lebanon, the development of power-sharing from semi-consociational to full-consociation (Aboultaif 2020) between the different sects was seen as an important step towards the production of the Taif Agreement, building on the earlier National Pact and long-standing practices which predated the country’s independence. Likewise, in Iraq, previous agreements between Shia opposition leaders and Kurdish elites on federalism and decentralization ensured that territorial power-sharing would be an important element of the new constitution. This agreement was, however, reached despite Sunni opposition, many of whom were either excluded or self-excluded from the constitutional discussions. Hence, domestic consensus was limited to two of the three main groups in Iraq. In both cases, there was a price to pay for domestic acceptance of the power-sharing deal: constructive ambiguity on questions such as second chambers (a Senate and Federation Council, respectively), deconfessionalization (in Lebanon) or the design of the federal system (in Iraq) allowed domestic elites to support an agreement knowing that some elements of it might not be implementable or might be implemented differently than initially intended. This would turn out to be a major challenge for the functionality and durability of both agreements.

Syria, on the other hand, demonstrates that no agreement will be reached if none of the main parties to a conflict see power-sharing as a potential solution, or lack incentives to move towards it. Here, there is neither a serious domestic discussion on power-sharing, nor any serious willingness amongst regime or the main opposition to agree to a power-sharing arrangement, even though the UN has tried to push for such an agreement through the Geneva process. We therefore argue that the entirety of domestic elites needs to be able to agree on the principle of power-sharing as an alternative to continued conflict. As the experience in Iraq demonstrates, inclusion of all the major groups in this domestic consensus is vital for avoiding new unrest and violence, and that partial agreement on power-sharing will result in partial implementation at best.

Figure 1: Conditions under which power-sharing get adopted

Negotiation in a second arena needs to reach convergence on power-sharing for an agreement to come into being. In Arena 2, international actors must see power-sharing as a credible and realistic solution to an ongoing conflict. International actors, be it the UN, specific countries or country blocs such as the USA or the EU, or regional powers such as Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran, must support power-sharing – by not only encouraging domestic actors, but by also ensuring that international negotiations amongst global and regional actors also promote a power-sharing solution. This can take different forms – in Iraq, the USA was the main driver behind the transitional constitutional framework and the new constitution, and it strongly supported the previously mentioned agreements between Kurds and Shia on federalism, as confirmed in our interviews. Likewise, our interviews in Lebanon highlighted how the USA and Saudi Arabia, along with Syrian acquiescence, all leant support to a power-sharing solution. A different trajectory emerges in Syria: neither Russia, the main international actor supporting the Assad regime, nor Turkey as the main international sponsor of the opposition, support an inclusive power-sharing settlement. Moreover, neither Iran nor USA have actively supported a power-sharing solution (Wieland 2021). Nonetheless, a ‘power-sharing oriented mediation’ was consistently – if weakly – pursued by the UN and its Special Envoys (Costantini and Santini 2022). Yet, it exists in tension with the Astana and Sochi forums, which have allowed Russia, Turkey and Iran to take a lead in discussions on ending the conflict. With a focus on regime victory, no serious proposals for permanent inclusive political settlement have come from various meetings, as confirmed in our interviews. In Syria, then, there is no convergence in Arena 2 on power-sharing as an acceptable solution, particularly since each power is satisfied with the status quo: the US has control over oil fields in the east, Turkey controls northern Syria to prevent the rise of a Kurdish political entity, Iran has established an important presence in Syria, and the regime has avoided defeat.

While domestic agreement on power-sharing, and international support for such a solution, are both necessary conditions for power-sharing adoption, they alone are not enough. Conflict actors frequently rely on the backing and support of their international allies and sponsors. Likewise, international actors carefully assess their involvement in conflicts, their allies and their strategic objectives. That is, rather than functioning as neutral arbiters, many external actors are taking sides, offering a range of supports, be it through military aid, financial support or political backing to specific domestic actors, who then act as their proxies on the ground. This is why research has demonstrated that international actors can hamper power-sharing arrangements, both during power-sharing negotiations and when these agreements are implemented (Walsh and Doyle 2018; McCulloch and McEvoy 2018). During the power-sharing mediation and negotiation process, international actors need to not only agree with one another (Arena 2), they must also engage with their proxies in such a way that power-sharing solutions, and associated agreements that support the final agreement on power-sharing, for example on security matters, are incentivized and eventually reached. This can occur, for example, through the provision of additional guarantees, as Syria became a major guarantor power in Lebanon after the Taif Agreement, ensuring that the Syrian government would push its allies in Lebanon to agree on a path towards ending the civil war. Likewise, American security guarantees for the Kurds before and during the constitutional negotiations in Iraq ensured that their focus on territorial autonomy were additionally backed up by the support of the most important international actor. This also helped address some (though not all) fears in relation to federalism leading to the secession of the Kurdish territories from Iraq, as both Iraqi officials and international advisers confirmed in our discussions.

Power-sharing agreements only come into being if a solution focused on elite cooperation and group rights protection is accepted across these three arenas. These arenas need to reinforce each other to open the space for a peaceful solution towards power-sharing to become acceptable to the different parties in the countries and to the main international actors involved in the conflict. Syria demonstrates the inability to gain consensus in and across the three arenas: no power-sharing solution has been agreed between domestic elites; international actors support different strategies for ending the war, and different dynamics between key international actors and their domestic proxies further complicate agreement. With the different sides either believing they can win the war militarily (the Assad-regime, backed by Russia and Iran, but also the Free Syrian Army and the opposition before the Russian involvement), or militarily and politically unable to change the current status quo (mainly Arab opposition around Idlib and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) under Kurdish leadership), there has been no space for serious discussions on how, and between whom, power-sharing could take place. As one international mediator argued, discussions never went beyond the agenda stage, with very little substance discussed in Geneva. There is also the recognition that the current status-quo is beneficial for numerous groups, with the regime beginning a normalisation campaign with its neighbours and Western powers, the opposition territories around Idlib benefitting from Turkish investment and development aid, and the AANES acting as a de-facto Kurdish autonomous territory.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Mediators in contemporary conflicts face numerous challenges. Comprehensive peace agreements have become far and few in-between in the last 10-15 years and failed constitutional transitions. As one international expert confirmed, even coming to an agreement on power-sharing, or starting the process of constitutional transition, seems to be ever-more difficult today, with success stories in cases such as Nepal and Kenya always coupled with failure in many other situations, such as in Sudan or Myanmar. Our framework for explaining power-sharing adoption highlights why agreement on constitutional transitions has become so difficult: more domestic actors believe they can either win conflicts militarily, either on their own or with support from external patrons, or they are content with, or unable to substantially change the status quo that mirrors a divided country without a final solution, as seen in the case of Cyprus, and more recently in Syria. Moreover, international actors no longer speak with one voice on power-sharing as a solution to ongoing conflict. New actors have emerged, with Russia, China, Turkey, Qatar, Iran and other regional actors now playing a major role in many of the ongoing conflicts around the world, for whom transition to democratic and inclusive governance is no longer the first response (see, e.g., Abboud 2021). Finally, domestic-international interactions have shifted. As one international expert told us about Syria, the regime only participated in the Geneva process because of pressure from Russia to be seen to be cooperating. But without the willingness of the regime to engage in meaningful negotiations, and with a lack of willingness (and possibly ability) of Russia to push the regime towards further concessions, these engagements in the peace process have been lukewarm at best. From all of this, our findings indicate several vital lessons for international mediators and academic experts involved in power-sharing negotiations around the world:

- Power-sharing agreements require convergence across three different arenas: amongst domestic elites; amongst international actors and amongst international elites and their domestic allies. Only when acceptability in all three arenas is possible can power-sharing agreements emerge and help end violent conflict. In this regard, it is important to consider how convergence in each of the three arenas and between them can be achieved. Here, international mediators can play a very important role, for example by ensuring that different discussions on power-sharing and other aspects of conflict resolution at the domestic and international level are connected.

- Finding agreement in the three arenas described above requires addressing the challenges posed by spoilers (domestic or regional actors), who either have no interest in a power-sharing solution, or whose interest lie in the continuation of conflict. As mentioned above, the Assad-regime and its international allies have acted mainly as spoilers in Syria, posing a challenge to the UN in its quest to reach an inclusive political settlement. Since power-sharing negotiations take place in multiple arenas, a strategy needs to be developed by international mediators, with the backing of the UN and other international actors, on how to engage with spoilers, and how to get their agreement to power-sharing in situations where this is the main pathway from ongoing conflict.

- Constructive ambiguity has been used by international mediators in Lebanon and Iraq to buy domestic and international agreement to the power-sharing deals in both countries. However, while this ambiguity has enabled the adoption of an agreement, particularly forging domestic buy-in of specific actors and contributing to consensus building in arena 1, it can create new durability problems in the implementation and functionality of the two power-sharing systems. Iraq’s dysfunctional federal system, and the failure of deconfessionalization in Lebanon are, at least in part, the result of this ambiguity, but they are also symbols of the lack of functionality of both power-sharing systems. While constructive ambiguity might well be needed to forge consensus, it is important that mediators consider its later impact in the implementation phase and its long-term effects on system performance.

[1] This contribution provides a summary of some of the findings of the project “Power-sharing for Peace? Between Adoptability and Durability in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq”, which has been funded by the Swiss Network for International Studies and included as its partners, swisspeace (lead), the Institute of Federalism, Switzerland, Brandon University, Canada, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, Lebanon, Peace Paradigms (Iraq) and the Arab Network for Development AAND, Lebanon.

References

Abboud, Samer. 2021. Making Peace to Sustain War: The Astana Process and Syria’s Illiberal Peace. Peacebuilding 9(3): 326-343.

Aboultaif, Eduardo Wassim. 2019. Power Sharing in Lebanon: Consociationalism since 1820. Routledge: London and New York.

Aboultaif, Eduardo Wassim. 2020. Revisiting the Semi-Consociational Model: Democratic Failure in Prewar Lebanon and post-Invasion Iraq. International Political Science Review, 41(1): 108-123.

Costantini, Irene and Ruth Hanau Santini. 2022. Power Mediators and the ‘Illiberal Peace’ Momentum: Ending Wars in Libya and Syria. Third World Quarterly 43(1): 131-147.

McCulloch, Allison and Joanne McEvoy. 2018. The International Mediation of Power-sharing Settlements. Cooperation and Conflict 53(4): 467-485.

McCulloch, Allison and Joanne McEvoy. 2020. Understanding Power-Sharing Performance: A Life-Cycle Approach. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 20(2): 109-116.

McEvoy, Joanne and Eduardo Wassim Aboultaif. 2022. Power-Sharing Challenges: From Weak Adoptability to Dysfunction in Iraq. Ethnopolitics 21(3): 238-257.

McGarry, John. 2017. Centripetalism, Consociationalism and Cyprus: The ‘Adoptability’ Question. Power-Sharing: Empirical and Normative Challenges, Allison McCulloch and John McGarry, eds. Routledge: London and New York, pp. 16-35.

Sisk, Timothy. 1996. Power-Sharing and International Mediation in Ethnic Conflicts. United States Institute of Peace: Washington D.C.

Walsh, Dawn and Doyle, J. 2018. External Actors in Consociational Settlements: A Re-examination of Lijphart’s Negative Assumptions, Ethnopolitics 17(1):21-36.

Wieland, Carsten. 2021. Syria and the Neutrality Trap. I.B. Tauris.

Further Reading

Aboultaif, Eduardo, Keil, Soeren and Allison McCulloch. (Eds.): Power-sharing in the Global South – Patterns, Practices and Potentials. Palgrave MacMillian: Cham.

Issaev, Leonid and Zakharov, Andrey. 2021. Federalism in the Middle East – State Reconstruction Projects and the Arab Spring. Springer Nature.

Salloukh, Bassel F. and Toby Dodge (eds). 2024. Special Issue on Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 30(1): 1-172.