Abstract

Conditional grants are also often seen as an instrument to reduce constituent units’ policy autonomy in federal systems. Conditional grant programmes also play an important role in policy-making in the EU. Cohesion Policy as an example of an EU public policy which has experienced a significant rise in conditionality instruments over recent decades. However, their use is controversial, as not all member states are affected by the set conditions in the same way which may undermining solidarity. Especially in federal and decentralised countries the autonomy of constituent units has been progressively limited. The constituent units are the main beneficiaries of EU cohesion policy, but they are not involved in decision-making on conditionalities and cannot be held accountable for compliance with all of them.

Conditional grant programs are widely used in federal systems to address the tension between decentralized policy provision and territorial equity, but conditional grants are also often seen as an instrument to reduce constituent units’ policy autonomy (Schnabel, Dardanelli, 2022).

The European Union, which operates through a hybrid system of intergovernmentalism and supranationalism, is not a federal system, but also faces tensions between member states’ policy provision and its treaty-based objective of promoting economic, social and territorial cohesion. To reduce these tensions, the EU uses its legal and (re)distributive instruments. The EU budget has often been considered too small to fulfil such an ambitious objective as territorial cohesion. However, due to the growing number of conditionality instruments, the EU budget has become an important tool for EU policy making beyond budgetary policy.

EU budgetary conditionalities are not new, in neither the internal nor external dimension, but conditionality of EU spending has become an important topic during recent years, first because of experiences during the economic and financial crisis (Bini Smaghi 2015, Jouen, 2015), later due to the refugee crisis in 2015 (Sacher 2019) and third due to the disregard of rule of law standards in some Member States (Miklóssy 2018; Closa 2019).

While conditional grants programs have been analysed in the literature on federalism and intergovernmental relations (e.g., Watts, 1999, Hueglin, Fenna, Schnabel, Dardanelli, 2022), conditionalities in the EU budget have not been systematically investigated. Although all major EU spending programmes are conditional in the sense that they have specified objectives, programming procedure and control systems, – I focus on EU Cohesion Policy as an example of an EU public policy which has experienced a significant rise in conditionality instruments over recent decades.

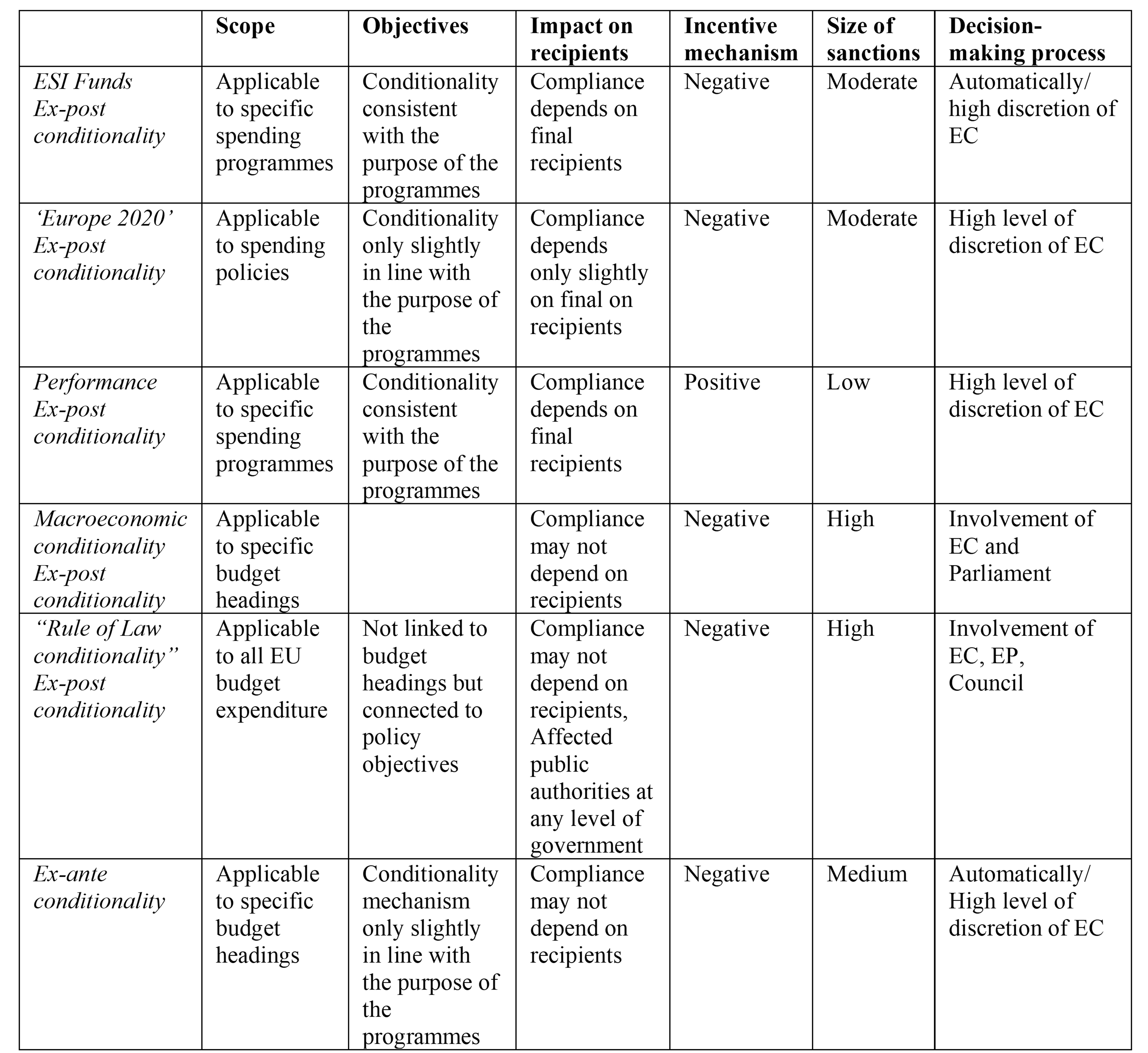

Within EU Cohesion Policy, conditionality is a governance instrument which interlinks specific requirements and the disbursement of EU spending and may, in a case of non-compliance, lead to the suspension or withdrawal of funds. The differences among the conditionality instruments are important and there are several indicators that help to assess conditionalities as policy instruments within Multiannual Financial Frameworks (MFFs). The analysis of the moment of application, the scope, objectives, impact on beneficiaries and any incentive mechanism, as well as the size of sanctions and the decision-making process applied to conditionalities, may help to explain the change in the budget introduced by these instruments.

Regarding the moment of application, conditionality instruments can be classified as ex-ante or ex-post conditionality. Ex-post conditionality means that the recipient of aid agrees to policy and institutional conditions that will be carried out and implemented after receiving the aid. The leverage mechanisms in ex-post conditionality relate to the interest of the conditionality recipient in continuing the beneficial cooperation (Koch 2015). Ex-ante conditionality refers to policy and institutional conditions which must be in place before the aid is disbursed. The interest of the recipient in receiving the benefit is used as a lever for a desired behaviour change (Koch 2015).

Regarding the scope, conditionalities may be applied to specific EU spending programmes, to specific spending policies or to all spending policies. The scope is reduced if a specific conditionality mechanism relates only to a specific spending programme, the scope is broader if all European Structural and Investment Funds (ESI Funds) are included, and the scope can be considered wide if all headings in the multi-year financial framework (MF) are related to the conditionality instrument (Kölling 2022).

In relation to the incentive mechanisms, those can be either negative or positive. Positive conditionality consists of the reception of benefits according to the fulfilment of conditions, whereas negative conditionality involves the reduction, suspension, or termination of benefits if the recipient no longer meets the conditions (Koch 2015).

Depending on the objective, conditionality may have a close and meaningful link to the spending area and be related to the same sector. Or the link may be less stringent and be crosscutting (Bachtler, Mendez 2020, 127).

In terms of the impact on the recipient, conditionalities could have a tangible and meaningful impact on the effectiveness of the spending or lie beyond the responsibility and control of recipients (Vita 2018).

The size of sanctions is of central significance among conditionality instruments: only if the costs of non-compliance exceed the costs of compliance can sanctions work (Schimmelfennig, Sedelmeier 2004).

In relation to the decision-making processes for sanction mechanisms, in the case of non-compliance these may be applied automatically, they can be decided by the European Commission (EC) after non-compliance or they may be applied after a long procedure in which the EC has to enter into dialogue with the recipient and the European Parliament (EP) where the application of sanctions needs the approval of the Council which may decide by the ‘standard’ voting method in the Council, qualified majority voting, or other voting procedures (Blauberger, Hüllen 2021).

After an empirical analysis of these indicators for conditionality instruments introduced from the MFF 1989–1993 to the MFF 2021-2027, the first finding is that during the past decades an increasing number of conditionality instruments have been applied in successive MFFs. The MFF for 2021–2027 (and even more NextGenerationEU) continues to increase the complexity and diversification of conditionality instruments. The increased use of conditionality in Cohesion Policy was not principally led by performance and accountability factors but partly due first to political spill-over from the Lisbon agenda (Mendez 2011), later to political spill-over from the effects of the eurozone crisis and finally to political spill-over from rule of law ‘backsliding’ in some Member States (Blauberger and van Hüllen 2021). Taking into account the moment of application, the scope, objectives, the impact on beneficiaries and incentive mechanisms, as well as the size of sanctions and the decision-making process applied to conditionalities, we can establish the following classification:

Table I: Conditionality mechanisms in EU Cohesion Policy

Source: Kölling 2022

A second finding is that conditionality instruments have changed over time. The analysis of the indicators helps to explain the change in the budget that is introduced by these instruments. Traditional ex-post conditionality mechanisms referred to the disbursement of funds according to specific indicators and targeted to specific objectives that were closely linked to the thematic area of spending. Analysing the subsequent MFFs, the link to specific spending programmes is seen as becoming increasingly loose, and compliance less related to the performance of recipients.

The third finding is that the increase in the use of ex ante conditionality instruments shaped traditional cohesion policy objectives and reduced the discretionary power of subnational actors in decision making in EU Cohesion policy. Moreover, conditionality in the EU budget has been decided mainly without the involvement of sub-national authorities.

The fourth finding is that the EU Funds are also increasingly used in order to incentivise institutional and policy reforms in Member States, and, in this context, conditionality has become an instrument for influencing Member States’ behaviour in areas of consensus-based soft governance and performance. The consequences of this in terms of perceived legitimacy, and for fulfilment of the treaty-based objectives of economic social and territorial cohesion are still to be explored.

The fifth finding is that the rule of law conditionality (general regime of conditionality for the protection of the EU budget) represents a new type of conditionality in EU policy instruments but does not represent a shift in the EU budget itself, although we may speak about an important change in the policy instruments. The rule of law conditionality is a specific ex-post conditionality which includes objectives that are not linked to budget headings but defines specific indicators which link breaches of the principles of the rule of law and the sound financial management of the Union budget. The compliance does not depend on the final recipients, but sanctions should take into account the potential impact on the final beneficiaries. The discretion of the EC is limited.

A sixth finding is that the EP, which in the past supported only performance-related conditionalities, was strongly in favour of the ex-post rule of law conditionality. This may also have consequences for the role of the EP in the decision making, e.g. on rule of law conditionality. However, the EP´s influence and capacity for scrutiny during decision making on conditionality instruments remain rather weak.

Conclusion

As in many federal states, conditional grant programmes play an important role in policy-making in the EU. However, their use is controversial, as not all member states are affected by the set conditions in the same way. Moreover, in federal and decentralised countries the autonomy of constituent units has been progressively limited. The constituent units are the main beneficiaries of EU cohesion policy, but they are not involved in decision-making on conditionalities and cannot be held accountable for compliance with all of them.

Suggested citation: Kölling, M. 2024. ‘The EU Budget and its Conditionalities ’, 50 Shades of Federalism.

* For the complete analysis see: Mario Kölling (2022): The role of (rule of law) conditionality in MFF 2021-2027 and Next Generation EU, or the stressed budget, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14782804.2022.2059654

References

Bachtler J., and C. Mendez. 2020. “Cohesion and the EU’s budget: Is conditionality undermining solidarity?” In Governance and politics in the post-crisis European Union, edited by Ramona Coman, Amandine Crespy, Vivien Schmidt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barca, F. 2009. An agenda for a reformed cohesion policy, A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations, Independent Report prepared at the request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy, Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/policy/future/pdf/report_barca_v0306.pdf

Bini Smaghi, L. 2015. “Governance and Conditionality: Toward a Sustainable Framework?” Journal of European Integration, 37(7): 755-768. DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2015.1079372

Blauberger, M., and V. van Hüllen. 2021. “Conditionality of EU funds: an instrument to enforce EU fundamental values?” Journal of European Integration 43(1): 1-16. DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2019.1708337

Closa, C. 2019. “The Politics of Guarding the Treaties: Commission Scrutiny of Rule of Law Compliance.” Journal of European Public Policy 26(5): 696–716. DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1477822

Hueglin, T. O., and Fenna, A. (2015). Comparative federalism ( 2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Jouen, M. 2015. “The macro-economic conditionality, the story of a triple penalty for regions.” Policy Paper 131, Paris, Institut Delors.

Koch, S. 2015. “A typology of Political Conditionality Beyond Aid: Conceptual Horizons Based on Lessons from the European Union.” World Development 75: 97-108, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X15000078

Kölling, M. 2019. “The EU budget between bargaining tool and policy instrument”, Features and challenges of the EU Budget: a multidisciplinary analysis, edited by U. Villani-Lubelli and L. Zamparini, 30-43, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Mendez, C. 2011. “The Lisbonization of EU Cohesion Policy: A Successful Case of Experimentalist Governance?” European Planning Studies 19(3): 519-537. DOI: 10.1080/09654313.2011.548368

Mendez, C., F. Mendez, V. Triga, and J. Carrascosa. 2020. “EU Cohesion Policy under the Media Spotlight: Exploring Territorial and Temporal Patterns in News Coverage and Tone.” Journal of Common Market Studies 58(4): 1034-1055. DOI: 10.1111/jcms.13016

Miklóssy, K. 2018. “Lacking rule of law in the lawyers’ regime: Hungary.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 26(3): 270-284.

Núñez Ferrer, J., C. Alcidi, R. Musmeci and M. Busse. 2018. Ex-ante conditionality in ESI funds: State of play and their potential impact on the financial implementation of the funds. Report for the European Parliament, Brussels.

Ovàdek, M. 2018. “The Rule of Law in the EU: Many Ways Forward but Only One Way to Stand Still?” Journal of European Integration 40(4): 495–503.

Rubio, E. 2020. “Rule of law conditionality what could an acceptable compromise look like?”, Policy Brief, Paris, Jacques Delors Institute.

Rubio, E. 2017. The next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) and its Flexibility. Report. European Parliament, Policy Department for Budgetary Affairs http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2017/603799/IPOL_IDA(2017)603799_EN.pdf

Sacher, M. 2019. “Macroeconomic Conditionalities: Using the Controversial Link between EU Cohesion Policy and Economic Governance.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 15(2):179-193.

Sapir, A., H. Wallace, P. Aghion, G. Bertola, M. Hellwig, J.Pisani-Ferry, D. Rosati, J. Vinals. 2004. An Agenda for a Growing Europe: The Sapir Report, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schnabel, J., and Dardanelli, P. (2022). Helping hand or centralizing tool? The politics of conditional grants in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Governance, 36( 3), 865– 885. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12708

Schimmelfennig and U. Sedelmeier. 2014. “Governance by Conditionality: EU Rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 11: 661−679.

Viţă, V. 2018. Conditionalities in Cohesion Policy, report. European Parliament, REGI Committee, PE 617. 498, Brussels.

Watts, R. L. (1999). The spending power in federal systems. Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University.

Further Reading

Bachtler J., and C. Mendez. 2020. “Cohesion and the EU’s budget: Is conditionality undermining solidarity?” In Governance and politics in the post-crisis European Union, edited by Ramona Coman, Amandine Crespy, Vivien Schmidt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kölling, Mario (2022): The role of (rule of law) conditionality in MFF 2021-2027 and Next Generation EU, or the stressed budget, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14782804.2022.2059654

Kölling, M., & Hernández-Moreno, J. (2023). The Multiannual financial framework 2021–2027 and Next Generation EU – A turning point of EU multi-level governance? Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2023.2241832

Schnabel, J., and Dardanelli, P. (2022). Helping hand or centralizing tool? The politics of conditional grants in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Governance, 36( 3), 865– 885. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12708